Why a Viral SaaS Churn Post Exposed a Bigger Problem in Dev Culture

It started as a small confession on Reddit and ended up as a kind of cultural Rorschach test.

A SaaS founder wrote that one of his “best customers”—paying $300 a month for 18 months—had canceled their subscription because they built it themselves. The founder added, with a note of wounded pride, that what they built was worse. Buggy. Incomplete. A downgrade.

The internet treated it like prophecy. Thousands of developers and product people rushed to crown a villain: AI. Vibe coding. The end of SaaS. The death of the engineer.

But the post didn’t say any of that. It wasn’t even about AI. The customer didn’t “vibe code” anything in an afternoon. They either hired a developer—or simply redeployed one already on payroll—and decided the economics of ownership beat the economics of rent. Most of the commentary missed that, because most never bothered to read the post.

The customer didn’t leave because they discovered a magical new tool. They left because they reached a quiet conclusion every buyer eventually reaches when software stops feeling like leverage: this is rent. And in a world where building alternatives keeps getting easier, rent eventually gets challenged.

The real story isn’t that AI is replacing developers.

AI—along with a tightening economy—is ending the easy era, exposing who understands customers, economics, and value… and who only understands code.

For many developers and product teams, the message is simple: school is over. Work is measured in outcomes. If you can’t translate your craft into a return for your employer and real utility for the user, your leverage disappears. If you can, you’ll be more valuable than ever.

TL;DR

- A viral Reddit post about a customer canceling a $300/month SaaS was widely misread as an “AI killed SaaS” story. It wasn’t.

- The real reveal is cultural: developer and product culture often lacks commercial acumen, and treats churn like betrayal instead of feedback.

- Complaining publicly instead of talking to users signals a deeper failure: detachment from how customers measure value.

- The “easy years” of being siloed, shipping features, and staying insulated from customers is ending—AI makes output easier, so value becomes the differentiator.

- The winners will be developers who become commercial: they talk to users, understand ROI, reduce bloat, and build what actually matters.

This article covers: developer culture, product managers, customer churn, SaaS pricing, AI deflation, feature bloat, founder-led sales, and the commercial skills required to stay relevant.

Key Takeaways

- A viral Reddit churn story was misread as “AI killed SaaS.” It wasn’t.

- The real reveal is cultural: many builders lack commercial acumen and treat churn as betrayal.

- Complaining publicly instead of talking to users signals detachment from customer value.

- The cushy era of staying siloed is ending—AI makes output easier, so value becomes the differentiator.

- The winners will be developers who become commercial: close to users, focused on ROI, and ruthless about bloat.

40,000 Developers Misread a SaaS Churn Story — And That’s the Real Warning

At its core, the original Reddit post was straightforward. A SaaS founder shared a candid story: one of his best customers, who had been paying $300 a month for a year and a half, canceled their subscription. Why? Because they chose to build their own internal version of the software.

The founder admitted, with a mixture of pride and disappointment, that what the customer had built was objectively worse—buggy, incomplete, a clear downgrade in terms of polish and features. Yet, the customer was happier. Why? Because the internal build aligned better with their specific needs and, crucially, the economics made sense.

The customer either hired a developer or repurposed an existing one on payroll, deciding that owning the software outright was more cost-effective than renting it through a subscription. This was the entire story, laid out in about two hundred words. It was thin, lacking of understanding to why one of their best customers simply walked and even as they assume prefered to spend more than their tool cost. It is an embarrassing professional admission by the author, but nothing to do with AI as the web would lean into.

By any reasonable count, the post and its derivatives have been shared and reposted well over 40,000 times across platforms, which makes the collective misreading harder to dismiss as noise. Maybe the right place to start is to ask how 40,000 developers—people who make a living reading code—couldn’t finish 200 words.

The irony is brutal: a community defined by precision and attention to detail in their craft failed to apply those same skills to a short, plain-text narrative. This is a glaring sign of professional illiteracy when it comes to context and nuance. Instead of parsing the actual content, the crowd defaulted to fear-driven assumptions, projecting anxieties about AI and job security rather than engaging with the reality of the story.

This reflexive victim mindset is more than a cognitive slip—it’s a symptom of unreadiness in a rapidly tightening market.

As AI accelerates and economic pressures mount, the luxury of insulated, output-only development is vanishing. The inability to read beyond the surface text signals a deeper discomfort with complexity and commercial realities. Many developers and product people may be ill-equipped to navigate the new landscape where understanding user value and business outcomes is not optional but essential. Without evolving this literacy, the profession risks being left behind.

What the post did not say, and never even hinted at, was anything about AI. There was no mention of “vibe coding,” no claims that artificial intelligence was disrupting SaaS or rendering engineers obsolete. Yet, somehow, the discussion exploded into exactly that narrative. Thousands of developers, product managers, and commentators took this brief confession and turned it into a prophecy of doom for software-as-a-service, all under the banner of AI’s rise. The irony: a community whose bread and butter is reading and writing code—textual precision—failed to read the actual text of a short post. They skipped the nuance and context and instead filled the vacuum with their own fears and assumptions.

This mass misreading is not just a funny anecdote about internet discourse; it’s a revealing symptom of a deeper cultural malaise within developer and product circles. It exposes a lack of commercial readiness—a discomfort, even an aversion, to engaging with the messy realities of business, user value, and economics. The reflexive victim mindset is on full display: churn is treated as betrayal, a personal affront, rather than feedback to be understood and acted upon. Instead of reaching out to the customer, learning why they left, and adapting, the knee-jerk reaction is to blame external forces—AI, market shifts, or some nebulous “end of an era.”

Why does this matter? Because we live in a moment where the stakes are higher than ever. AI is real and accelerating; economies are tightening; layoffs and team compressions are becoming the norm. The luxury of insulated development—where code is king and user engagement is optional—is evaporating. Those who cannot read beyond the code, who cannot translate technical output into commercial outcomes, risk obsolescence. The post’s viral misinterpretation is a canary in the coal mine, signaling a profession struggling to evolve its mindset.

But here’s the pivot: the real lesson of that Reddit post is not about AI or technology replacing developers. It’s about customer value and ownership economics. It’s about understanding why a customer would choose to stop paying for a polished product in favor of a rough, self-built alternative. It’s about recognizing that software is not just code; it’s a lever for business outcomes. And it’s about confronting the uncomfortable truth that developer culture has often been detached from the users it serves, insulated by layers of abstraction and a focus on features rather than utility.

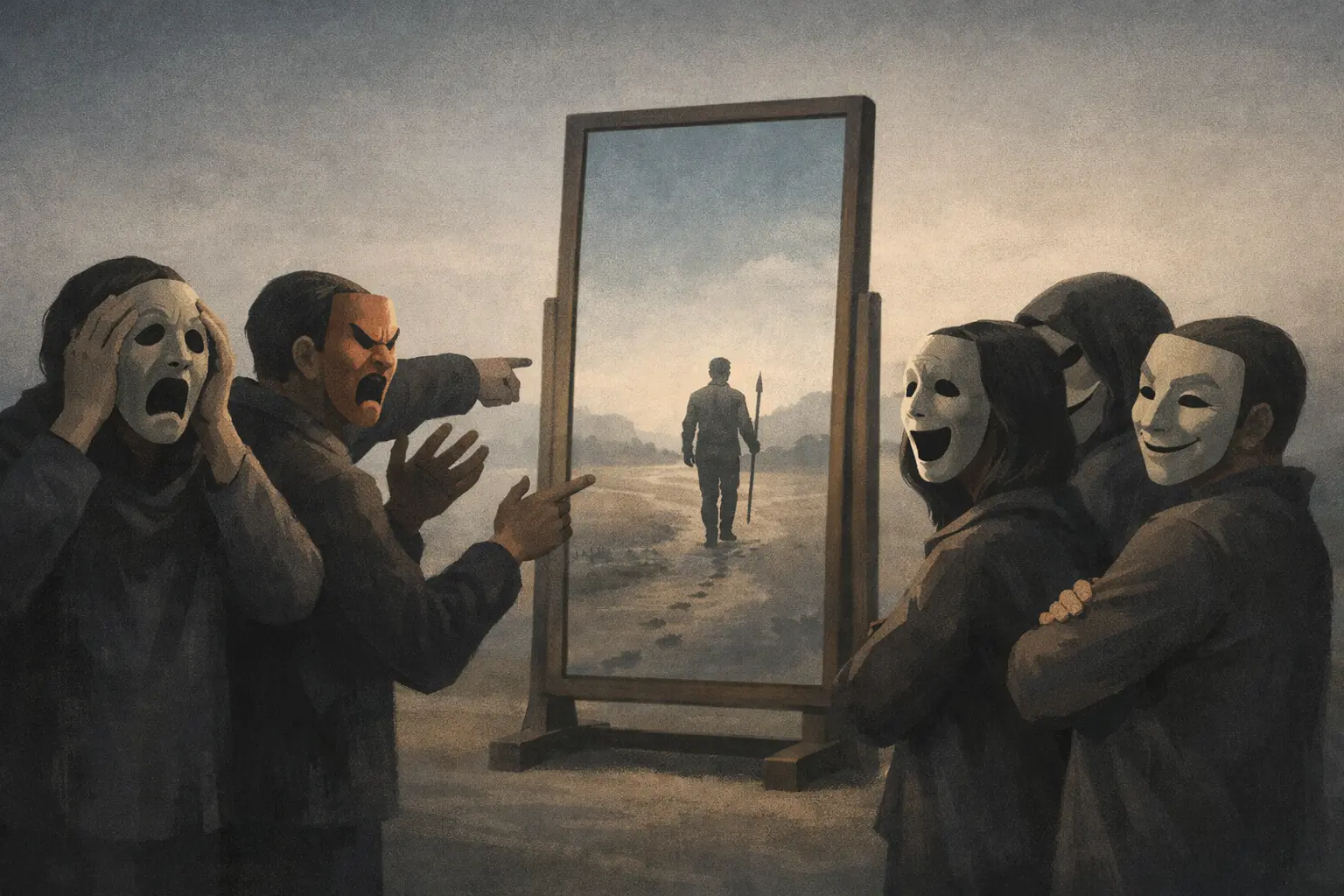

This detachment breeds complacency and blinds teams to the true drivers of success. When churn is seen as an attack rather than an insight, when product bloat is tolerated instead of questioned, the result is a slow erosion of relevance. The post was a mirror held up to the industry, reflecting a profession at a crossroads: continue down the path of shipping-only development, or embrace the harder, more rewarding path of commercial empathy and value creation.

As we move forward, the conversation shifts from misplaced fears about AI to a deeper examination of rent versus leverage—the economics of owning your tools versus renting them—and how feature bloat and adoption patterns play into this dynamic. Understanding these forces is key to navigating the new landscape of software development, where survival depends not just on writing code, but on delivering real, measurable value.

Your Best Customer Didn’t Leave Overnight — You Just Didn’t Notice

The widespread misreading of the Reddit post was not merely a lapse in attention—it exposed a profound blind spot, one embodied by the founder’s own reaction. The narrative of a “best customer” disappearing without warning transcends simple churn; it is a stark indictment of how some founders fundamentally misunderstand—or worse, dismiss—the very people sustaining their business.

How does a “best customer” vanish without a trace? Especially one paying $300 a month for 18 months—a relationship that should have been closely managed, deeply understood, and actively nurtured? The contradiction is glaring. If this customer truly was the “best,” why were there no warning signs? No alerts from product usage data, no flags from customer success teams. In mature SaaS operations, these signals are the lifeblood of retention strategies. Their absence reveals either a startling lack of insight or willful blindness. It is the difference between a captain who navigates by instruments and one who ignores the dashboard until the ship runs aground.

High-performing product teams don’t outsource customer intimacy to dashboards. They institutionalize it. They build direct contact into the operating rhythm—calls, reviews, demos, escalation loops—so the user’s voice is never fully abstracted into charts. This proximity prevents internal echo chambers and forces teams to confront reality early, when small corrections are still possible. Instrumentation tells you what happened. Conversation tells you why.

Airbnb’s founder Brian Chesky famously employed Disney-style “Snow White” storyboarding to map the entire customer journey, aligning teams around shared customer experience goals. This visual narrative helped break down complex interactions into relatable scenes, enabling every department to understand and improve the user’s experience holistically. By embedding empathy through storyboarding, Airbnb transformed abstract data into actionable insights that guided product and service decisions.

Similarly, Stripe’s CEO Patrick Collison invites a customer to the first 30 minutes of every bi-weekly leadership meeting to deliver candid feedback directly to the executive team. This practice ensures that customer voices remain central to strategic decisions. As of 2024, Stripe processes $1.4 trillion in payments annually and serves half of the Fortune 100, a testament to how customer-centric leadership can scale impact.

The SaaS market’s complexity compounds these challenges. According to the Pendo 2019 Feature Adoption Report, just 12% of features generate 80% of daily usage, while 80% of features remain rarely or never used. Similarly, Zylo’s 2025 SaaS statistics reveal that 53% of SaaS licenses go unused, translating into $21 million wasted annually across organizations. These figures underscore a brutal truth: product bloat is endemic, and customers often engage with only a narrow slice of a product’s capabilities. The customer’s internal build—rough and buggy as the founder admitted—was precisely tailored to their needs, cutting through the noise and complexity. They did not value the hundred features the product offered; they needed two that worked flawlessly. This classic SaaS paradox pits sprawling, polished products against customers who crave sharp, focused tools. The decision to build internally was not impulsive but strategic—a reclaiming of control over a cumbersome, generic, and ultimately expensive tool.

Churn almost never comes out of nowhere; it is typically preceded by leading indicators such as usage decay, declining seat utilization, negative shifts in support sentiment, silence from internal champions, and increased scrutiny from procurement teams.

ChurnZero’s customer health score handbook notes that the purpose of health scoring is to surface churn risk early—often while there is still time to intervene—by translating behavioral signals like declining engagement into an actionable forecast rather than a retrospective explanation.

Best-in-class SaaS organizations systematically track these signals through customer health scores and renewal risk dashboards, enabling proactive interventions before churn occurs. Industry leaders like Gainsight and Totango emphasize the critical role of health scoring in detecting renewal risk early, long before churn becomes inevitable.

The founder’s failure here wasn’t technical—it was interpretive. And it’s the same failure the dev crowd displayed in the comments: a reflex to react before reading, to protect ego before confronting reality.

Furthermore, the $300 monthly spend signals an early-stage SaaS customer, where founder proximity should be highest. At this scale, the relationship is personal, and the founder’s role extends beyond product development to active customer engagement. Ignoring this proximity betrays a fundamental misunderstanding of early customer dynamics. In startups, every customer counts, and the founder’s direct involvement is often the difference between retention and churn.

This principle aligns with the Y Combinator ethos articulated by Paul Graham in “Do Things That Don’t Scale,” which advocates founder-led sales and deep personal engagement with early customers. At this price point, founders should remain intimately connected to revenue streams and churn signals, leveraging direct relationships to refine product-market fit and drive growth.

Ownership brings a premium beyond cost savings. It confers control over features, timelines, and priorities; customization that molds the tool to fit unique business contours rather than forcing adaptation to a one-size-fits-all product; and risk reduction—no dependence on vendor roadmaps, pricing shifts, or existential threats like vendor insolvency. These incentives are potent, especially amid an economic environment marked by massive uncertainty. The ongoing wave of layoffs—over 150,000 reported in 2024 alone, with the trend continuing into 2025—has heightened scrutiny on every dollar and minute spent. Rent is convenient; ownership is empowerment.

Yet, rather than confronting these realities, the founder chose mockery and public grievance. The tone, steeped in wounded pride and dismissive of the customer’s build as “worse,” reeks of arrogance. This defensive stance blames the customer instead of embracing a vital learning opportunity. Arrogance in founders and developers is corrosive; it kills curiosity and blinds teams to uncomfortable truths. It erects barriers to feedback and stifles growth. This is not merely a personal failure but a strategic blunder. Publicly lamenting churn without introspection alienates the very audience critical to understanding it. It signals contempt, not curiosity—a fatal flaw in any customer-centric business.

Contempt for customers is the silent killer of SaaS companies. It breeds complacency, blinds teams to real problems, and fosters toxic cultures where feedback is met with defensiveness rather than action. The founder’s post revealed less about the customer’s choice and more about his inability to face hard realities. It exposed a mindset trapped in output over outcome, features over utility, and ego over empathy.

Ultimately, the departure of this “best customer” was not a sudden betrayal but a slow unraveling, invisible to a founder who refused to look. It was a quiet vote of no confidence in a product that ceased to feel like leverage and began to feel like rent. The real tragedy is not the loss itself but the failure to anticipate it and the failure to learn.

When your best hunter isn’t coming back to feed the village, it’s because they fashioned their own spear—one better suited to the hunt they face.

As the industry confronts these lessons, the core truth remains: contempt kills learning. This founder’s blind spot is emblematic of a broader dev and product culture that prizes output over insight and ego over empathy. Without reckoning with this mindset, the cycle of detachment and denial will persist. The world developers wish still existed is ending—and understanding why is the next imperative.

The End of the Easy Tech Era: Perks, Prestige, and the Collapse of the Silo

There was a moment—roughly 2015 to 2022—when being a developer or product manager felt like joining a priesthood. If you could ship features and speak fluently about systems, you could live inside a protected economy where the rules of gravity didn’t apply. Companies grew at all costs. Teams expanded like empires. Budgets were an assumption. Perks were theatre: snack walls, massage credits, brand-new MacBooks, entire internal merch stores dedicated to employees who hadn’t yet built anything meaningful. A tier-one logo on your résumé didn’t just get you a job—it became a kind of passport. You were set for life. Business Insider and The New York Times have both documented how lavish perks—from microkitchens and massage credits to in-office laundry and endless snacks—became part of the recruiting arms race, and how those perks are now being unwound in the efficiency era.

And the culture that formed in that period was predictable: confidence hardened into entitlement. Not everyone—there are exceptional teams and humble builders—but enough that it shaped the norms. Developers and product managers began to view customer conversations as “someone else’s job,” and commercial accountability as an inconvenience. Growth would continue forever. SaaS budgets would keep rising. You could be siloed, ship your tickets, and still win.

The details matter because they weren’t metaphors—they were policy. Google has been reported to shutter microkitchens and swap higher-end snacks for cheaper alternatives as it tightens costs. Meta has repeatedly trimmed perks and meal programs during its “year of efficiency,” even as it pushed for greater performance intensity. Business Insider has described the broader shift as the end of “the good life,” noting that the pullback on perks coincides with layoffs and a management posture that has the upper hand for the first time in many workers’ careers.

That world is ending.

Not with a bang, but with receipts. Compensation has already shown the shift: Levels.fyi’s 2022 end-of-year report found median total compensation in the U.S. dropped across the board compared to 2021, with software engineers down 2.2%—small in isolation, but historically meaningful as the first real break in the “always up” story. TrueUp’s tracker shows the scale of the correction: 239,101 people were impacted by tech layoffs in 2024, and 209,838 in 2025 so far. This isn’t a storm you wait out. It’s a climate.

If you want a single case study for the new era, look at what happened at Twitter—now X—after Elon Musk took over. The company’s workforce was cut dramatically within months, with roughly 6,000 employees laid off following the acquisition, according to court filings and reporting on the ensuing severance lawsuits. Musk publicly pushed a ruthless performance standard—calling engineers into late-night code reviews and repeatedly signaling that titles, credentials, and process were secondary to shipping working software. Whatever you think of the man, the message to the broader market was unmistakable: the era of bloated headcount and ticket-shuffling as a career is over.

The tone shift is visible in the small stories, too. Business Insider’s reporting on the “perks grift” era—including Meta’s “Grubgate,” where employees were fired for misusing meal vouchers—reads less like gossip and more like a symptom: when abundance becomes normal, people start treating benefits like entitlements and the company like a vending machine. In the new era of layoffs and scrutiny, that behavior doesn’t survive—because the margins don’t exist to tolerate it.

The shift shows up in the smallest places first. The “easy era” wasn’t only high salaries; it was the ability to hide. A developer could stay inside code and still be valuable because output was scarce. A product manager could live inside roadmaps and Jira and still rise because teams were large and the organization could afford inefficiency. Today, teams shrink while expectations grow. AI increases the output ceiling, meaning “I shipped it” is no longer the differentiator.

No more hiding.

The differentiator is: did it matter?

And that brings us back to the Reddit post.

The reason it was misread so aggressively—and why tens of thousands of developers and product managers projected their fears onto it—is because it threatened the identity built in that old world. It wasn’t just a churn story. It was a reminder that customers can leave silently, and that ownership can beat polish, and that value is not measured in features shipped but in outcomes delivered. That’s not a comfortable thought if your professional life has been structured to avoid customers.

This is where the culture becomes dangerous—not because it is harsh or unkind, but because detachment starts to look like sophistication. “We’re builders,” people say, as if builders don’t need to know what the building is for. “Sales and support handle that.” “We shouldn’t have to talk to customers.” The implication is always the same: the work is beneath us.

Amazon built an operating system to prevent that kind of detachment. Its “working backwards” process starts not with a roadmap, but with a draft press release and FAQ written as if the product already exists—forcing teams to articulate the customer problem, the measurable benefit, and why the user should care before a single sprint is planned. The discipline is blunt by design: if you cannot explain the value in plain language, you do not understand it well enough to build. It’s customer obsession, but it’s also an anti-bloat mechanism—because it makes it harder to hide behind activity when the only question on the table is outcomes.

Paul Graham wrote about this in his essay “Do Things That Don’t Scale,” warning founders not to fall into the myth that building a great product is enough—that if you build it, users will automatically come. Instead, in the early stages, founders have to do unscalable things: personally recruit users, talk to them, sell them, learn from them, and be uncomfortably close to the truth.

And the uncomfortable reality is that many developers and product managers have become, culturally, allergic to outcomes. They want their value to be assumed rather than proven. They want the organization to provide meaning and direction rather than demanding it from them. They want to remain in the bunker of technical identity while the market shifts outside. They want to be insulated. And insulation is a luxury the new market no longer funds.

And that’s the core cultural fracture: the old world rewarded specialization and insulation; the new world rewards integration and accountability. It rewards people who can move across silos. Who can speak to customers, translate their needs into product decisions, and quantify the value created. Who can understand not just what can be built, but what should be built, and what the customer will actually pay for. No more passengers.

The tribe metaphor is useful here, because cultures repeat. When a tribe lives in surplus for long enough, it begins to forget why its tools exist. The rituals become performative. The hunters brag about their spears. The planners argue about new designs. The village grows comfortable. Then winter arrives, and the tribe realizes too late that comfort was never the point. Survival was. Surplus does not last forever. Winter always arrives.

The Reddit post reaction matters because it was a cultural tell. The fear, projection, and victimhood weren’t about AI; they were about the end of the bargain many thought they had signed: “I’ll build, and the market will keep paying.” That bargain is broken. Customers are more sophisticated. Alternatives are cheaper. Teams are leaner. Output is commoditizing. And the only safe place left is commercial value—measured, defensible, and felt by the user.

If you’re a developer or product manager who still believes customer conversations are beneath you, you are standing on the wrong side of history. In the old world, you could hide behind process and prestige. In the new world, you will be audited by reality: by churn, by usage decay, by budgets tightening, and by teams that can no longer afford passengers. The market is not hiring for siloed excellence anymore. It is hiring for people who can see the whole system—customer, product, economics, and outcomes—and who can explain, in plain language, why their work creates value.

And that brings us to the next, unavoidable conclusion: in the age of cheap AI and abundant alternatives, SaaS can no longer justify rent without leverage—because customers can now build their own spears.

AI Deflation vs SaaS Inflation: Why $300/Month Tools Are Getting Challenged

The best way to understand what’s happening to SaaS pricing is to stop thinking in moral terms—fair or unfair—and start thinking in physics. Price is a function of alternatives. And AI has detonated the cost of alternatives.

For roughly $20 a month, a single employee can now access a frontier model that can write, summarize, classify, translate, brainstorm, analyze spreadsheets, draft contracts—and generate working code. Claude Pro sits in the same bracket, and Anthropic now offers power-user tiers at $100 and $200 per month for people who hit limits because the tool is becoming part of their daily workflow. Against that baseline, it is increasingly difficult to defend $300 per month for a narrow SaaS feature—especially if the feature is, at its core, a wrapper around capabilities that are now cheap, abundant, and improving.

This isn’t a moral complaint. It’s a pricing strategy failure. Too many SaaS businesses are still pricing as if they live in a world where building is expensive, switching is painful, and customers are loyal by default. That world is gone.

The spear-building story wasn’t a one-off—it was the market rehearsing the future.

The Deflation Curve: More Capability, Less Cost

The price of frontier AI models has not just declined—it has collapsed, even as their capabilities have soared. In 2021, the published input cost for using GPT-3 was $0.06 per 1,000 tokens, or $60 per million tokens. At the time, this was considered a fair price for state-of-the-art language generation, and many SaaS tools built their cost structures and pricing assumptions around these economics. That was the baseline many SaaS businesses quietly priced against.

Fast forward to 2024, and OpenAI’s GPT‑4o mini now offers input pricing at just $0.15 per million tokens. That’s not a typo: from $60 to $0.15 per million tokens. This represents a staggering 99.75% decline in the unit cost of “intelligence” for basic language tasks—while the models themselves have become dramatically more capable. To put it plainly: what once cost tens of dollars now costs less than a single coin.

This deflation isn’t just about price—it’s about the explosion in capability. GPT‑4o is not only far more accurate and reliable than GPT-3, but it’s also multimodal: it can handle text, images, audio, and more, all in a single model. The qualitative leap is enormous, even if it’s hard to quantify in a single percentage.

And OpenAI is not alone. Anthropic, Google, and other major players have entered the market with their own highly competitive models and aggressive pricing. Open-weights models like Llama are pushing costs down further, while local models are becoming viable for many tasks, reducing switching costs and making it easier for customers to substitute or roll their own solutions. The result is a landscape where capability is abundant and the barriers to entry are lower than ever.

And then there’s the pressure that doesn’t show up on an invoice. Open‑weights models like Meta’s Llama can be run at near‑zero marginal cost once you have the hardware, and models like DeepSeek are explicitly designed to be deployed flexibly—including locally—through open releases and broad platform availability. The fastest-growing category of “alternatives” isn’t another SaaS vendor—it’s a competent internal team with an open model, a prompt library, and enough infrastructure to keep data inside the firewall. In that world, the price anchor is no longer your monthly subscription. It’s the cost of inference and the decision to own.

DeepSeek has already pushed the market into a price war. Reuters reported that the company cut prices by as much as 75% during off‑peak hours—exactly the kind of aggressive deflationary move that forces every competitor to respond, whether they want to or not.

When the cost of intelligence collapses, rent-seeking software has nowhere to hide.

AI deflation is visible in public price sheets. SaaS inflation is visible in renewal quotes.

The customer is waking up—and they’re doing the math.

A Deflation Timeline (and Why It Breaks SaaS Pricing Assumptions)

If this feels abstract, put it on a timeline. The most important detail isn’t the unit—it’s the direction of travel: the cost of language intelligence falls by orders of magnitude while capability expands.

Even using conservative published price anchors, the collapse is brutal:

| Year | Example model / pricing anchor | Approx. cost per 1M input tokens | Capability note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | GPT‑3 published input price | ~$60 | Baseline: strong text generation |

| 2024–25 | GPT‑4o mini input price | $0.15 | Higher quality + multimodal family |

| 2024–25 | Google Gemini 3 Flash input price | $0.50 | Cheap fast model widens baseline expectations |

| 2024–25 | Anthropic Claude Haiku input price | $1.00 | Higher-quality alternative anchors competition |

| 2025 | Open‑weights (Llama) run locally | ~$0 marginal (after hardware) | Ownership + privacy, no vendor rent |

| 2025 | DeepSeek models (open + ultra‑low cost) | Price-war pressure | Frontier‑class alternative forces cuts |

(GPT‑4o mini pricing; Gemini 3 Flash pricing; Claude Haiku pricing; DeepSeek local/open availability.)

This is why “pricing like it’s 2018” isn’t just a stylistic mistake—it’s a structural error. The user’s baseline expectation is being trained by the most competitive market on earth: the AI model market.

To see how quickly the floor has dropped, look at what the raw building blocks cost today.

The Cost of Capability Has Collapsed

| Provider / Model | Input Cost (per 1M tokens) | Output Cost (per 1M tokens) |

|---|---|---|

| OpenAI GPT‑4o mini | $0.15 | $0.60 |

| Google Gemini 3 Flash | $0.50 | $3.00 |

| Google Gemini 2.5 Pro | $1.25 | $10.00 |

| Anthropic Claude Haiku 4.5 | $1.00 | $5.00 |

(OpenAI GPT‑4o mini pricing; Gemini 3 Flash pricing; Gemini API pricing; Claude Haiku 4.5 pricing.)

These numbers matter because they change the entire build-vs-buy conversation. If the “intelligence layer” in your SaaS costs cents to dollars at scale, the customer will naturally ask: what am I paying $300 a month for?

What used to cost tens of dollars per million tokens is now measured in cents.

Now anchor that to what users are being trained to expect.

| Product | Monthly Price |

|---|---|

| ChatGPT Plus | $20 |

| Claude Pro | $20 |

| Claude Max | $100 / $200 |

(Claude Max pricing.)

When the most powerful general-purpose cognitive tools on earth are priced at $20 a month, “premium SaaS” needs to justify itself in a way it never had to before.

The Build vs Buy Math Has Flipped

In 2021, the cost of building anything non-trivial was high enough that “just pay the SaaS bill” was often rational. In 2025, for many workflow features, that logic is reversed.

Take a simple example: transaction categorization. Imagine a finance team wants to classify one million transactions per month into categories and flag anomalies. If you used GPT‑4o mini for the core classification step, your raw input/output cost could be measured in single-digit dollars per million tokens, depending on how compact your prompts are. Even if you run multiple passes, add a second model for verification, and include some overhead, you’re still talking about tens of dollars—not hundreds.

So why does a niche SaaS charge $300 a month for it?

Because most SaaS pricing still reflects a 2018 cost structure—while the customer is now living in 2025.

In the old world, the answer was simple: the software was hard to build, hard to maintain, and your team didn’t want to own it.

That question is not theoretical. It’s exactly the question embedded in the viral Reddit story. The customer didn’t leave because the tool was worse. They left because ownership felt safer than rent.

The Free Tier Arms Race

If you want to see the pressure in real time, look at how generous free tiers have become.

Free tiers used to be token gestures—enough to test, not enough to rely on. Today, free tiers are often enough to live on. The reason is simple: competition forces generosity.

Every category now has a credible free alternative, a cheaper competitor, or an open-source substitute. And because AI lowers the cost of capability, the marginal cost of serving “free” users is falling too. So companies push the free tier outward, hoping to win mindshare and monetize the heavy users later.

But there’s a second-order effect: conversion gets harder.

This isn’t just anecdotal. Pricing leaders have been flagging for years that in saturated categories, the hardest part is no longer acquisition—it’s convincing a free user that the incremental value is worth paying for. Paddle’s State of SaaS Pricing report notes that pricing and packaging have become central to retention and growth precisely because the old “upgrade later” playbook is less reliable in a competitive market.

When free tiers solve most of the job, fewer users feel urgency to pay. This is why pricing is shifting away from feature gates and toward usage intensity. Anthropic’s Max plans—$100 and $200 tiers designed specifically for “power users”—are the clearest signal of where monetization is heading: the free and low-cost tiers capture the broad base, while the high-usage tail funds the business.

And this is the trap for SaaS that prices like it’s 2018: it assumes user loyalty will fill the gap. It assumes customers will “upgrade eventually.” It assumes the relationship is sticky.

Users aren’t loyal. They’re rational.

And the moment the math flips, they move.

Raising Prices as Users Flee

When SaaS businesses feel churn, the most common response is to raise prices. And the data suggests that this is not an edge case: a Vertice report cited by CFO Dive found SaaS prices increased 12% on average over a 12‑month period, and that 73% of vendors raised prices since August 2022.

Vertice’s 2025 SaaS Inflation Index goes further: it estimates SaaS now costs roughly $9,100 per employee, up from $8,700 in 2024 and $7,900 in 2023—nearly a 15% increase over two years.

Blue Ridge Partners’ 2025 pricing guidance notes that mid-sized software companies were increasing prices around 12% and becoming more aggressive about packaging changes—evidence that the “raise prices to offset churn” playbook has become normalized across the market.

It’s an understandable reflex: you lose users, you extract more from the ones who remain. You tell yourself the product is improving, the market is maturing, the “value” is higher.

But in a deflationary capability environment, this move is often self-defeating. It accelerates the very behavior you fear: switching, downgrading, and building in-house.

We’re already seeing this logic play out at the platform level. In 2025, Denmark’s Ministry of Digital Affairs began moving away from Microsoft Office 365 toward LibreOffice, citing sovereignty and dependence risk, with reporting noting similar moves in parts of Germany. The point isn’t that Microsoft is failing. The point is that even the most entrenched software categories are no longer immune to the build-vs-buy and dependence calculus.

At the same time, CFOs have become far more explicit about what they believe SaaS is worth. Zylo’s research, reported by CFO Dive, found that unused SaaS licenses cost small companies an average of $2 million annually and large enterprises an average of $127 million—waste so large that seven in ten respondents said reducing it is their top SaaS management priority. When procurement teams are staring at that level of shelfware, price hikes don’t feel like “value capture.” They feel like a tax on inattention.

If governments are willing to consider the friction of leaving Microsoft Office, the average SaaS vendor should not assume it has pricing power.

- Users underutilize the product.

- The vendor adds more features to justify price.

- Users ignore the new features.

- The vendor raises prices anyway.

- The user leaves—quietly—or builds the spoon.

Pricing strategy becomes an internal narrative rather than an external truth.

Dev/Product Culture and Pricing Delusion

This connects directly back to the broader cultural argument.

Misaligned pricing strategies are rarely born in finance. They are born in product rooms.

Builders justify price increases based on effort rather than outcomes. Roadmaps become legal arguments: look what we shipped, therefore pay us more. And because many product and engineering teams avoid customers, they never see the real usage patterns that would force humility.

So the organization begins to price itself according to its own self-image, not according to the customer’s lived reality.

That is how you end up with a $300 product being canceled by a customer who is happier with a worse internal version.

They weren’t buying perfection. They were buying control.

The Only Sustainable Premium: Leverage

SaaS can still charge premium prices—but only if it provides durable leverage that the customer cannot cheaply replicate.

That leverage is not “more features.” It is:

- compliance and auditability

- trust and security

- deep integration into workflows

- reliability at scale

- reduced operational risk

- network effects

If you provide leverage, you can justify rent.

If you provide capability, you will be deflated.

And AI is turning capability into a commodity faster than most companies are willing to admit.

The future belongs to teams that price honestly, build leanly, and stay close enough to customers to notice the moment their spear gets sharpened elsewhere.

And, crucially, the ability to deliver outcomes that the customer cannot easily achieve on their own, even with access to cheap, abundant AI.

This is the new reality: the only sustainable premium in SaaS is leverage. Everything else is just rent—and rent gets challenged when the cost of alternatives collapses.

The Commercial Builder: Why Technical Brilliance Isn’t Enough Anymore

Technical brilliance—the elegant algorithms, the sleek code, the ingenious architectures—has become the cheapest commodity in software. What was once a fortress of competitive advantage is now a baseline expectation, easily replicated and accelerated by AI.

Code is cheap now.

There is no longer any excuse for builders to hide behind virtuosity while staying ignorant of the customer. If you think coding skill alone will save your product, you’re already losing. The real edge today is commercial proximity: knowing your customers’ pain, reading their silent signals, and relentlessly hunting for truth in the messy terrain of human experience.

This isn’t a shift. It’s a reckoning. The old playbook that glorified technical genius as the highest virtue is bankrupt. AI has commoditized craftsmanship, and the market punishes those who ignore the human side of the equation.

The spear is no longer the product alone—it’s the intimate knowledge of the hunt, the tribe, and the shifting landscape where value is created or destroyed. Builders who cling to abstraction and distance are not just out of touch—they are obsolete. The new builder is uncomfortable by default, a commercial hunter who thrives in the friction of real user engagement.

Let’s be clear: technical brilliance is now table stakes. Every junior developer can summon code with AI’s help; every team can deploy infrastructure with a few clicks. The moral failure is to treat this as an excuse for commercial ignorance. If you’re not living in the discomfort of customer proximity, you’re not building—you’re playing pretend.

This section exposes why customer proximity beats brilliance, how Amazon’s Working Backwards is a cultural weapon against ego, why founder-led sales is the antidote to product delusion, and what Airbnb’s founder mode teaches about delegation and immersion. It also unmasks friction as the silent churn engine and delivers a hard-edged checklist for builders ready to shed complacency and win.

Proximity Beats Brilliance

The cult of technical brilliance is seductive because it’s visible, measurable, and offers a clear status path. But it’s also a trap. Technical virtue signaling—showing off elegant code or complex algorithms—has become a form of status behavior that masks commercial failure. It’s a way for builders to appear indispensable while ignoring the only thing that actually matters: customers. This is self-sabotage.

No more passengers.

Technical brilliance without customer proximity is like a spear without a hunter: sharp but aimless, impressive but irrelevant. It’s the equivalent of building a flawless weapon and then throwing it blindfolded into the forest. The market doesn’t reward code elegance alone; it rewards solving real problems for real people. Builders who cling to technical virtue as a shield against customer engagement are courting irrelevance.

Distance is denial.

Proximity is not a checkbox or a quarterly survey. It’s a relentless, embedded presence in the customer’s world. It means listening deeply, learning continuously, and adapting swiftly. Jeff Bezos nailed it: “We’re not competitor obsessed, we’re customer obsessed.” This obsession is not optional; it’s existential. Without it, a product’s technical polish is a relic waiting to be outflanked.

Consider the spear and the hunter. The spear—the product—is useless without the hunter’s intimate knowledge of the terrain. Builders must become hunters who don’t just sharpen tools but learn the landscape intimately, sensing shifts before competitors do. This is the brutal truth the new builder must face.

What Amazon Got Right: Working Backwards

Amazon’s “Working Backwards” process is a cultural filter designed to crush ego and bloat. Instead of launching into development with a laundry list of features or grandiose technology roadmaps, teams start with a press release and a FAQ document, written as if the product already exists. This forces brutal clarity on customer benefits and business rationale before a single line of code is written.

This discipline is a hedge against the “build it and they will come” delusion that plagues so many startups. It demands that builders confront the question: who benefits, and why? It transforms development from an internal ambition into a customer-driven mission. Bezos put it plainly: “Start with the customer and work backwards.”

Working Backwards also serves as a cultural gatekeeper. It exposes inflated egos and bloated ideas early, before costly development. If you can’t write a clear, compelling customer narrative, your idea isn’t ready. This ruthless filter keeps teams honest and focused, preventing the common trap of building shiny objects that no one wants.

A particularly powerful element is the fictional customer quote embedded in the PR/FAQ. It forces the team to picture a real human using the product, not a spec sheet. When AWS launched S3, the imagined founder said, “With S3, I can store all my data securely without managing hardware, and scale instantly.” This vivid customer reality guided every technical choice, ensuring the product served a clear need.

Founder-Led Sales Was Never About Hustle—It Was an Information System

Paul Graham’s essay “Do Things That Don’t Scale” is often misread as a call for founder hustle. The truth is more profound: founder-led sales and unscalable customer work are early-stage information systems designed to shatter product delusion and gather raw, unfiltered user data.

This direct engagement is not about growth metrics; it’s about brutal learning.

Dashboards don’t sell.

Early founders who answered support emails, held one-on-one calls, or conducted demos weren’t hustling—they were mining for insights that no analytics dashboard could reveal. This was the crucible where product-market fit was forged.

Unscalable work is the antidote to the dangerous myth that product success can be engineered from a distance. Graham’s wisdom is timeless: “The only way to find a product that fits is to do things that don’t scale.” If you avoid this messy, uncomfortable work, you’re not building a product—you’re chasing a mirage.

Four unscalable but invaluable actions exemplify this: manually onboarding customers to understand unique workflows; meticulously documenting support interactions to detect patterns; customizing products or pricing to test hypotheses; and personally following up on churn to uncover hidden reasons. These labor-intensive steps are irreplaceable for understanding the customer’s lived experience.

Airbnb’s “Founder Mode” Lesson: Stay in the Details

Brian Chesky’s “Founder Mode” philosophy is a damning indictment of the delegation culture that dominates many startups. Chesky famously said, “You have to be in the details, or you’re not really building the company.” At Airbnb, this meant Chesky and his co-founders personally handling customer support, photographing listings, and even hosting guests.

Founder Mode is about immersion, not abdication. It’s a direct challenge to the modern tendency to outsource customer understanding to analytics dashboards and third-party vendors.

Chesky’s experience reveals that true empathy and urgency arise only from firsthand engagement with users’ messy realities.

Delegation culture breeds complacency and distance. It creates layers of abstraction between builders and users, diluting urgency and blunting insight. Founder Mode demands discomfort and presence, forging intuition and strategic clarity. Builders who embrace it wield their spear with both technical skill and commercial wisdom.

Friction Is the Silent Churn Engine

User friction—the small, often invisible obstacles that slow or confuse users—is the silent engine driving churn and eroding lifetime value. FullStory defines friction as “any point in the user journey where the experience is slowed, confused, or interrupted”; Contentsquare echoes this, noting friction leads to “drop-offs, frustration, and ultimately lost revenue”.

Friction is the hidden tax on the user’s time and trust. Unlike vocal complaints, friction often causes silent churn—users quietly leaving or downgrading without feedback. Proud builders, enamored with their code and architecture, often miss this. They see perfection in their work where users see obstacles.

Friction is the hidden tax on the user’s time and trust. Unlike vocal complaints, friction often causes silent churn—users quietly leaving or downgrading without feedback. Proud builders, enamored with their code and architecture, often miss this. They see perfection in their work where users see obstacles.

This blindness is a fatal flaw.

Friction is invisible to those who build in isolation but glaringly obvious to users navigating the product. The antidote is relentless friction hunting: combining quantitative analytics with qualitative interviews, session replays, and direct feedback. Builders who commit to this discomfort create smoother, stickier experiences that customers choose to stay with, even when cheaper alternatives exist.

The Uncomfortable Checklist (What Elite Builders Do Differently)

Elite builders don’t just tolerate discomfort—they weaponize it.

They go where the truth is.

They reject abstraction and distance, choosing instead to live in the tension between code and customer truth. Here are eight behaviors that separate the elite from the complacent:

- Start Every Project with a Customer Press Release: If you can’t write a clear, compelling press release and FAQ with a fictional customer quote before coding, you’re not ready to build. Stop hiding behind vague specs.

- Embed Yourself in Customer Interactions Weekly: If you think talking to customers is beneath you, you’re already on the path to irrelevance. Get on support calls, read emails, watch session replays. No shortcuts.

- Do One Unscalable Thing Every Week: Embrace the grind of manual onboarding, bug triage, or direct follow-up. If you avoid unscalable work, you’re avoiding truth.

- Map the User Journey End-to-End: Identify every friction point with data and qualitative feedback. Prioritize fixes that kill silent churn engines. No excuses.

- Write Pricing and Packaging Narratives from the Customer’s View: Stop justifying costs internally. Tell stories of value and outcomes that resonate with real users.

- Regularly Challenge Your Assumptions with Customer Data: Use surveys, interviews, and analytics to test hypotheses ruthlessly. Be ready to pivot or prune features.

- Celebrate Small Details that Compound: Reward teams for fixing minor annoyances that improve retention, not just launching flashy features.

- Make Commercial and Technical Teams Co-Owners of Customer Truth: Break down silos so engineers, product managers, and sales share the same insights and urgency. Disunity kills.

Developers and product managers who think customer conversations are beneath them are the biggest threat to their own products. The market doesn’t fund that arrogance anymore. This arrogance is a death sentence in a world where proximity is power.

The spear is useless if you refuse to learn the terrain.

The new builder is uncomfortable by default because they choose proximity over distance, empathy over abstraction, and learning over certainty. They wield their spear not just with technical skill but with commercial wisdom and humility. Bezos warned long ago, “If you double the number of experiments you do per year, you’re going to double your inventiveness.” Graham warns, “It’s better to make a few users really happy than hundreds of thousands kind of happy.” Chesky insists, “You build a company by building a product people love, and you can’t do that from a conference room.”

The market will fund teams that hold code and customer truth in the same head. When the tribe ignores that truth, the spear-makers are always the last to notice.

Separation Breeds Indifference: What the Viral Post Really Revealed

The original post, brief and straightforward, was never intended as a grand statement. Yet its impact came from exposing a fundamental contradiction within a community fluent in code and skilled at understanding complex systems. Here was a message, barely two hundred words, plainly addressing the human realities behind software development. Yet it went largely ignored by those who claim expertise in the digital languages they use daily. The irony: those who pride themselves on interpreting complicated code failed to engage with a simple, honest note about the very people their work is meant to serve.

This failure to read, to listen, is not just an oversight. It reveals a deeper professional gap in the tech world—a complacency born of separation, a professional identity increasingly shaped by abstraction rather than connection. The problem is not only that many have become inattentive to the human side of their craft but that this inattentiveness has hardened into disregard for the customer. It is a disregard not always conscious but no less damaging because of its invisibility. The customer becomes a vague concept, a checklist of requirements, rather than a real person involved in the ongoing process of product development.

Separation breeds indifference. When those who build products are removed from those who use them by layers of hierarchy, jargon, and procedure, the signals that matter are lost or dismissed. Friction is minimized as mere annoyance, feedback is filtered through technical perspectives that erase nuance, and the product itself becomes an end rather than a tool. This cultural gap is the enemy of innovation. It erodes empathy and dulls the builder’s sense of purpose. No matter how elegant the code or clever the design, the product fails if it does not meet the real, often messy, needs of its users. Users notice.

The old markers of professionalism—clean pull requests, elegant patterns, technical skill—have not disappeared, but they no longer suffice. Not anymore. The economy has shifted, demanding new forms of value and new ways to define what it means to be a builder. In this new landscape, usefulness is measured not in lines of code or architectural purity but in the lived experience of users. The builder is no longer a distant artisan perfecting their craft in isolation but an engaged participant in a complex ecosystem of human needs and commercial realities. This requires humility before the complexity of human behavior, before the unpredictability of markets, and before the fact that expertise is never complete.

Value is not what you ship. It’s what people keep paying for. Profit is the real proof of relevance.

Professionalism now demands proximity—not just physical closeness, but emotional and intellectual engagement. It means listening more than lecturing, valuing discomfort as a sign of relevance rather than a threat to authority. It calls for a recalibration of values, a recognition that craftsmanship divorced from commerce is incomplete, and that the sharpness of the spear is meaningless without the hunter’s intimate knowledge of the terrain. This is not a call to abandon skill or rigor but to integrate them with empathy and a grounded understanding of the world beyond the keyboard.

There is no grand epiphany here, no easy transformation waiting just beyond the horizon. The path forward is incremental and often uncomfortable, requiring professionals to confront their own blind spots and to relinquish comforting myths of technical elitism. That is the hard part. Mastery, in this sense, is not a static achievement but a continual process of learning from the messy, unpredictable realities of users. It demands a culture that values unscalable work—not as a burden but as an essential source of truth. It asks for a renewed commitment to presence, to engagement, and to the hard, often unglamorous work of translating insight into impact.

In the end, the market will not reward those who cling to abstraction and separation. It will favor those who embody the new professionalism: those who are commercial, close, and humble. The spear remains a potent symbol—its power lies not in the steel but in the hands that wield it, hands that know the ground beneath their feet. This is the underlying reckoning of our moment: proximity is power, and humility is strength.

The future belongs to those who understand that building products, like living, demands presence, empathy, and the courage to face discomfort head-on. The post was never the point; it was a mirror held up to a culture that must choose between complacency and connection. Mastery without empathy is just noise. The sharpest spear is useless without a hunter who knows the land.

FAQ

What was the Reddit post actually about?

A customer paying $300/month canceled a SaaS subscription and built a rough internal version instead. The story wasn’t about AI—it was about the economics of ownership and value.

Why did so many developers interpret it as an AI story?

Because many commenters didn’t read the post carefully and projected fears about AI replacing jobs. The misreading exposed a deeper cultural problem: reacting before understanding context.

What does the post reveal about developer and product culture?

It revealed a lack of commercial acumen—churn treated like betrayal, customers treated like abstractions, and value treated as something assumed rather than measured.

Why is the “easy era” ending for developers and product managers?

AI increases output, economies are tightening, and teams are shrinking. In that environment, outcomes matter more than activity, and proximity to customers becomes a competitive advantage.

Why does SaaS pricing feel increasingly misaligned?

Because AI capability is deflating rapidly while many SaaS vendors continue raising prices. As alternatives get cheaper, customers become more willing to switch or build internally.

Why is churn usually predictable?

Churn tends to follow leading signals like declining usage, weaker engagement, and fading internal champions. Mature SaaS companies track these indicators before the renewal is lost.

What does “commercial developer” mean?

It means builders who talk to users, understand ROI, challenge bloat, and build what actually matters. In the current environment, commercial literacy is a career moat.