The Press Release Scam in Web3

Why paid wire distribution is not PR, rarely helps SEO, and quietly damages credibility.

Press releases in Web3 are a waste of your money. Based on years of experience, there’s at best a 0.5% chance—a generous estimate—that a press release will generate meaningful positive impact for your project. More likely—around 80% of the time—they cause harm by draining resources and creating negative signals about your website to bots and search engines. The remaining 19.5%? No impact at all. This isn’t a hot take; it’s a position proven by logic, data, and real-world examples after watching this industry burn money on press releases and get nothing back.

The tiny 0.5% exception occurs when the story is genuinely newsworthy—such as a major partnership with a Tier-1 company like NVIDIA announced on a quiet day. Even then, any exposure gained is minor and burns out quickly. The real value comes from the underlying news itself, not the press release.

Disclosure: This is editorial analysis based on years of industry experience and research into press release distribution and PR outcomes in Web3. This article is for founders, executives, and marketers who need to make informed decisions about PR and marketing spend.

That your money often comes from venture capitalists or token holders who expect returns. Founders and executives are accountable for how these funds are spent. Yet, the press release ecosystem in Web3 doesn’t even deliver noise; projects pay for content that’s not read. Releases frequently send negative signals to search engines and large language models due to backlink patterns and templated structures. Writers lack strategic know-how, so these releases provide near-zero contextual value to bots or agents. It’s a dead end.

This article will prove this claim with clear logic, data, and real-world examples—not just opinion. It is written for founders and executives who need to make informed decisions, junior marketers who need ammunition to push back against ineffective vendors, and managers responsible for driving accountability in their teams.

At VaaSBlock, our mission is to help Web3 projects shed the scammy, amateur reputation that press release spam perpetuates. Changing this dynamic is one of the highest-leverage moves the industry can make to build real credibility and lasting success.

In the sections ahead, you will learn:

- Why press releases in Web3 don’t deliver value and often cause harm

- How vendors exploit vanity metrics, and the inexperience of CMOs with SEO myths to sell ineffective products

- The psychological, myths and economic forces driving this wasteful cycle

- What real PR looks like and why it matters

- Practical steps projects can take to stop burning money in the press release trap

“This is a scam — the vendors are lying about the outcomes.” — Ben Rogers

Quick definitions (so we’re talking about the same thing)

- Press release: A written announcement intended to inform journalists and the public. In regulated industries it’s also a disclosure instrument. In Web3 it’s often used as paid distribution content.

- Newswire / wire distribution: A paid syndication service (PR Newswire, Business Wire, GlobeNewswire, etc.) that republishes your release into partner endpoints and publisher “press release” containers.

- Earned media: Coverage a journalist chooses to write, in their own words, with reporting, skepticism, quotes, and context.

- Paid media: Ads and sponsored placements where distribution is purchased and performance is measurable.

- PR (professional practice): Relationship-driven reputation strategy that earns attention, not buys it — and ties communications to measurable business outcomes.

One‑Minute Summary Press releases in Web3 are widely misused and misunderstood; worse, the industry has adopted the false belief that a press release equals PR. Marketers and projects don’t understand the original purpose of a press release or how to measure its impact. Originally designed for transparent, fair, and regulated disclosure, press releases have devolved into a costly, low-impact marketing default deployed by amateurs. Vendors sell “distribution” that does not lead to eyeballs or engagement, hiding behind vanity metrics and SEO myths to peddle their grift. Theoretically, a press release should earn coverage measured by inbound inquiries from journalists working on organic stories; instead, any inbound is from opportunistic business developers trying to sell the project their scammy products. The psychology of hitting the “publish” button feeds a credibility economy benefiting vendors, not projects. Real PR is a strategic, relationship-driven practice—nothing like the mass press release spam flooding inboxes today. Projects should recognize red flags and redirect budgets toward initiatives that actually generate results. Web3 press releases could be considered the most expensive and ineffective media spend in the world. In other words: most crypto press release spend is a measurable loss, not a strategy.

The Fire Sale: Press Releases as the Default Waste in Web3

Press releases persist in Web3 for the same reason cheap fireworks survive in tourist towns: they’re loud, they’re easy, and they create the illusion that something important just happened.

For founders, a wire release is a fast way to manufacture the appearance of momentum. It gives you a link to paste into Telegram, a screenshot to circulate with investors, and a shiny “As seen on” badge for your homepage — all without the friction of earning real attention. For junior marketers, it becomes an easy deliverable and a hard one to challenge, especially when leadership has already decided that “PR” means “getting published somewhere.” That mindset is backwards — especially when you’re spending other people’s money. A press release only works when it contains real news, the kind of story a publication can run and expect readers to click, because attention is what keeps newsrooms alive.

That’s why press releases in Web3 aren’t just ineffective — they’re a tell. They signal a team that doesn’t know how earned media works, and a leadership group that mistakes activity for traction, mistaking a distribution receipt for credibility. Motion is not momentum — and optics are not marketing.

“I can’t know for sure, but it would surprise me if serious journalists have not blacklisted any release containing ‘Raised X’ or ‘Strategic Partnership’ to help them cut through the clutter.” — Ben Rogers

Then there’s the second illusion: SEO. Many Web3 CMOs justify releases as “link building,” as if a handful of wire pickups will boost rankings and build authority. SEO tools and search guidelines paint a different picture. Press-release-style links are typically tagged nofollow or sponsored, duplicated across low-value endpoints, and contribute negligible authority. If you want your domain to rank, you need real editorial mentions, real citations, and real links earned because people actually chose to reference you.

(Ahrefs;

Semrush)

If press releases don’t earn journalistic attention, and they don’t meaningfully strengthen your search footprint, the only remaining justification is exposure — the hope that your announcement reaches potential users or investors. But the moment you admit that, you’re not buying PR. You’re buying media. And media is measurable, which means press releases must compete against performance channels that can prove clicks, conversions, and outcomes. That comparison is brutal.

From Newswire to Nowhere: “Published” Doesn’t Mean “Covered”

In Web3, the phrase “we got published” has become a kind of ritual. A founder posts a screenshot of a Yahoo Finance page. An agency drops a “featured on Business Insider” badge into the pitch deck. A CMO forwards the link in Slack like it’s proof of legitimacy.

But that’s not how journalism works and it’s not even how most of these pages get created. In Web3, that confusion is often reinforced by press release distribution vendors (including PR Newswire crypto packages) who blur syndication with coverage. Treating a press release as “coverage” is the LinkedIn equivalent of announcing a grand new title that no one asked for and no one is impressed by. In reality, most founders and CMOs don’t even think this far; they buy releases because they’ve seen others do it, and because the industry rewards the appearance of legitimacy. It’s the oldest question in management, answered badly, over and over: if one kid jumps off a bridge, would you? In Web3, the answer is often yes — and it’s a deeper indictment of how little strategic thinking goes into marketing decisions, especially when the spend comes from other people’s money.

You write it, pay a wire service to distribute it, and the wire syndicates it into a network of endpoints that accept press-release feeds. Those endpoints include publisher “press rooms,” investor-relations subfolders, and sponsored content sections that are designed to ingest large volumes of releases automatically. Most of it is never reviewed by an editor. Most of it is never read.

This is why a press release can appear on a respected domain without ever being covered by that publication. It’s not an endorsement. It’s not editorial. It’s closer to a bulletin board — corporate copy pinned to a trusted brand’s wall.

If you want to see the difference in the wild, look for the labels: “Press Release,” “Sponsored,” “PR Newswire,” “GlobeNewswire,” “Business Wire,” or “Provided by.” Those labels are the publisher telling you — in plain English — that the content was not reported, edited, or written by their newsroom. It’s uploaded copy.

Muck Rack’s State of Journalism 2025 report shows most journalists ignore the majority of pitches they receive, and that relevance is the dominant filter — not volume. (Muck Rack)

Axios reported in 2024 that major PR agencies are moving away from impression-based reporting toward outcomes and verifiable readership — the exact opposite of what wire vendors sell. (Axios)

There is a simple test for whether a publication actually covered you: did a journalist write about you as part of a broader story, using their own words, with quotes, context, and skepticism? Or did your copy appear verbatim under a “press release” label with a wire logo attached? One is earned media. The other is self-publishing with a receipt.

Next, we’ll map where these releases actually land — and why “appearing” there is not the same as being read.

What follows is not a conspiracy; it’s infrastructure.

Large publishers often maintain press-release ingestion pipelines because they’re cheap to run and they monetize the long tail. In practice, it becomes an easy revenue stream: publishers can monetize inexperienced buyers while isolating the low-quality content in clearly labeled folders that protect the core site’s reputation. A wire service pushes copy into a feed, the feed populates a labeled page, and the publisher collects ad impressions from whoever stumbles across it. The newsroom doesn’t touch it.

That’s why the same release can “appear” across dozens of respected domains without being read by any meaningful audience. It’s not coverage — it’s placement inside a press-release container.

Below are common examples of where these releases land, what they are, and how to spot them.

Table: Where press releases actually appear (and what it means)

| Publisher / Domain | Where the release appears | What it is | What vendors imply | Reality check | What to look for |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yahoo Finance | Press Release / Provided by (wire label) | Automated wire feed page | “Featured on Yahoo Finance” | A syndicated press-room page, not editorial coverage | “Provided by”, “Press Release”, wire logo |

| Business Insider | PRNewswire / GlobeNewswire feed pages | Wire republish / paid content container | “Covered by Business Insider” | Copy published verbatim under a wire label | “PR Newswire”, “GlobeNewswire”, “Sponsored” |

| MarketWatch | Press Release pages via PRNewswire / Business Wire | Wire ingestion | “MarketWatch wrote about us” | MarketWatch hosted your wire copy; no reporting | “Press Release”, “Provided by” |

| Benzinga | Press Releases / Newsfile / Accesswire / PRNewswire | Feed ingestion + sponsored | “Benzinga feature” | A labeled press release endpoint | “Press Release”, wire attribution |

| Morningstar | GlobeNewswire / Business Wire press pages | Wire republish | “Morningstar coverage” | Wire copy syndicated into a press section | “GlobeNewswire”, “Business Wire” |

| StreetInsider | Press Release archive | Bulk ingestion endpoint | “Picked up by media” | Low-traffic press-release archive | “Press Release”, wire tag |

| Seeking Alpha | Press release pages / newswire ingestion | Automated ingestion | “Seeking Alpha article” | A wire copy page, not analysis | “Press Release”, “Provided by” |

| Crypto pubs (Cointelegraph, Bitcoinist, etc.) | “Press Release” category | Paid / submitted copy | “Media feature” | A labeled paid placement, often templated | “Press Release”, “Sponsored”, disclosure |

If your agency sells you a slide full of logos based on this table, understand what you’re looking at: not media coverage, but a series of automated endpoints that borrow credibility from the host domain.

Because it means the value of the product is not readership. There is no value.

In the next section, we’ll quantify the cost of that adjacency — and show why it collapses the moment you compare it to real performance media.

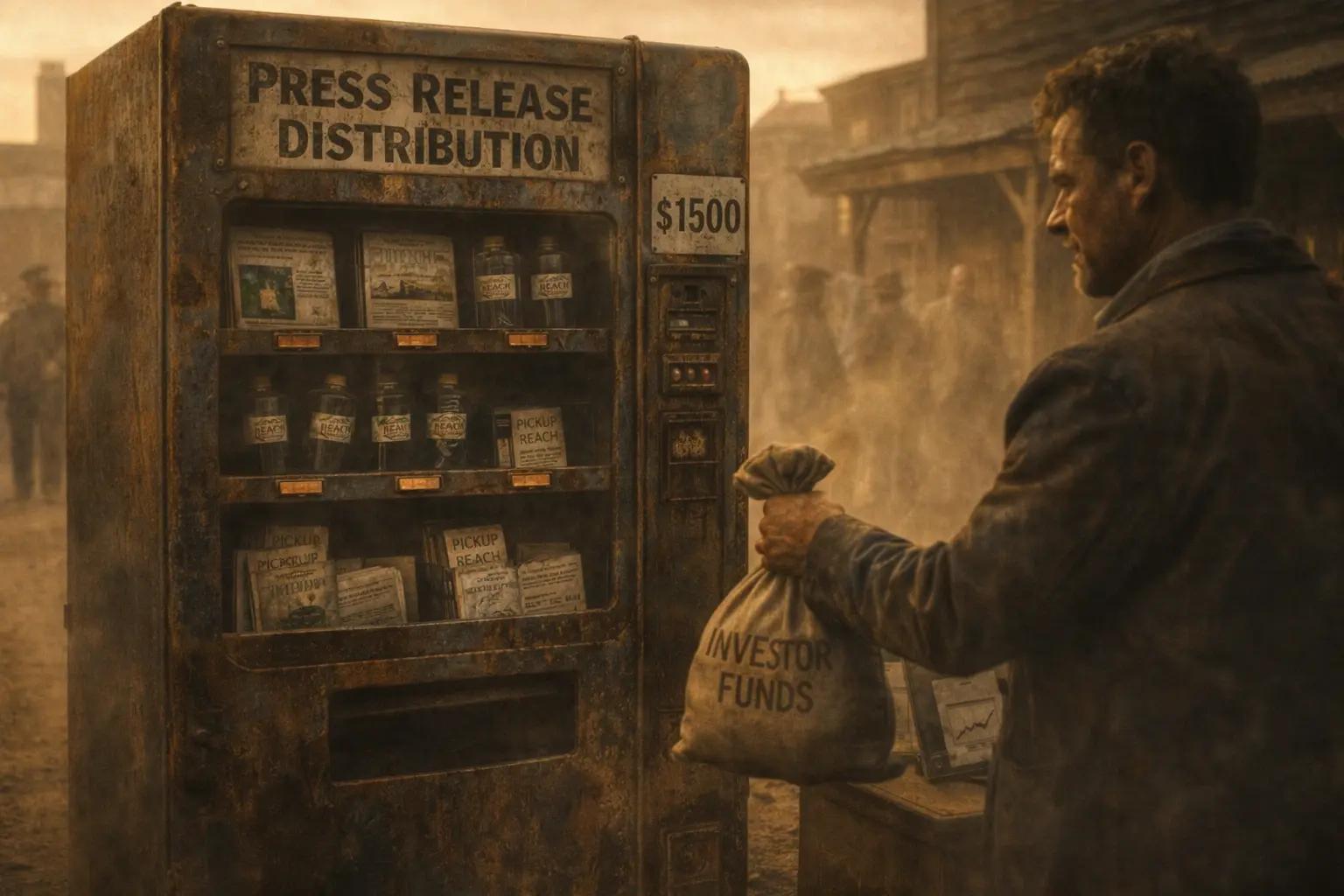

Cost vs. Click: When $1,500 Buys You a Screenshot

Once you accept that a press release is not PR, the only defensible way to evaluate it is the same way you evaluate any other paid channel: what did you get for the spend?

That framing changes everything, because it forces the press release industry to answer questions it was designed to avoid.

This is where the press release economy becomes embarrassing.

In any serious marketing organization, the first question is not “Did we get published?” It’s “What did we buy?” and “What happened next?”

Press release vendors avoid that framing because it forces their product into a category it can’t survive: paid media.

Most wire services price distribution like a premium advertising product while refusing to provide the standard evidence that premium media is expected to deliver: audience definition, verified impressions, click-through rates, time-on-page, conversion attribution, and cost-per-outcome.

To make the comparison explicit, here’s what you’re actually choosing between.

Table: Press releases vs performance media (what you pay for, and what you can measure)

| Channel | Typical pricing model | Typical cost range | What you can measure | What you actually get |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wire press release distribution (GlobeNewswire / PR Newswire / ACCESS / EIN) | Flat fee per release or package | ~$400–$2,000+ per release depending on scope and add-ons | Often limited or opaque; basic pickup reports; some vendors offer click tracking | A labeled press-release page syndicated across endpoints; brand halo via host domains |

| Programmatic display ads (open web) | CPM auction | ~$2–$12 CPM depending on targeting and inventory | Impressions, CTR, viewability, frequency, conversions (via pixels) | Guaranteed distribution to a defined audience; measurable performance |

| Search ads (Google / Bing) | CPC auction | ~$0.50–$10+ CPC depending on competition | Clicks, conversions, CPA, ROI, keyword performance | High-intent traffic from people actively searching |

| Social ads (X / LinkedIn / Reddit) | CPC / CPM auction | Varies widely by platform and audience | Clicks, conversions, audience breakdowns, CPA | Targeted reach + measurable outcomes |

| Sponsored content / native ads (reputable publications) | Flat fee + tracked distribution | ~$1,500–$15,000+ depending on publication | Pageviews, time-on-page, CTR, sometimes lead capture | Editorial-style placement with measurable distribution |

The critical point is not that performance media is always “cheap.” It’s that it is accountable. You can start with low bids, test creative, refine targeting, and scale only when you see outcomes. CPC auctions adjust based on competition for your audience; you pay more when the audience is valuable, and less when it isn’t.

Press release vendors, by contrast, sell a fixed-price product that behaves like unverified media. They promise “reach,” but they rarely define the audience or prove engagement, and they often frame the absence of tracking as a feature.

If you’re going to spend $1,500, you should be able to explain exactly what you bought — and whether it moved a real metric.

If a vendor can’t show you the numbers, you’re not buying marketing. You’re buying comfort.

In the next section, we’ll look at the tracking loophole vendors hide behind, and why “privacy” is the most convenient excuse in the world when your results are close to zero. What $1,500 Buys You in Measurable Media

The easiest way to expose a press release vendor is to run a simple thought experiment: take the same budget and spend it through a channel that is designed to be measured.

Here’s the uncomfortable math.

Quick calculator:

- $1,500 at $5 CPM = ~300,000 impressions

- $1,500 at $10 CPM = ~150,000 impressions

- $1,500 at $2 CPC = 750 clicks (or 375 clicks at $4 CPC)

In programmatic display, CPMs commonly fall in the single digits, especially for broad awareness campaigns. At $5 CPM — a conservative midpoint inside the $2–$12 range reported across open-web programmatic buying — $1,500 buys roughly 300,000 targeted impressions. Even at $10 CPM, you still buy 150,000 impressions, with controls for frequency, geography, and audience definition. Even if the average click-through rate on display is modest, you still get real data: impressions served, CTR, frequency, and on-site behavior.

In search advertising, cost-per-click works through auction dynamics: you’re bidding against other advertisers targeting the same intent. Benchmarks vary widely by industry, but Google Ads CPC averages commonly land in the low single digits, with many categories clustering around $1–$4 (WordStream, Google Ads Benchmarks 2024). At $2 per click, $1,500 buys 750 visits from people actively searching; at $4 per click, it buys 375 visits — and every one of those visits can be tracked through to downstream actions.

And unlike press releases, those channels report CTR and conversion behavior by default — which is the bare minimum for accountability.

This is the accountability gap wire vendors cannot survive. When you spend $1,500 on measurable media, you can quantify impressions, clicks, on-site behavior, and conversions. When you spend $1,500 on a press release, the vendor often hands you a pickup report and calls it “reach.”

That’s why the pricing model is the tell: performance channels price outcomes through auctions, while press release vendors price optics through flat fees.

Citations (benchmarks): WordStream “Google Ads Benchmarks 2024”; Google Ads Help “How the Google Ads auction works” ; Smart Insights “Display advertising CTR benchmarks”

The Pricing Illusion: Flat Fees, Hidden Add‑Ons, and the Cost of “Reach”

Press release vendors rarely present their product like advertising, because advertising invites accountability. Instead, pricing is framed as “distribution,” “reach,” or “visibility” — words that sound like outcomes while carefully avoiding any promise of measurable performance.

When the product can’t defend itself on outcomes, the sales strategy shifts to language — and the language is doing most of the work.

Some vendors are unusually transparent. ACCESS Newswire publishes subscription plans that start at **$714 per month** for **one press release per month**, with higher tiers at **$934** and **$1,315** per month and “Plus” upgrades that include up to three releases per month ( ACCESS Newswire pricing) . EIN Presswire publishes tiered press release packages on a public pricing chart and promotes “detailed distribution reports” as part of its offering (EIN Presswire pricing: ). Business Wire also offers published pricing plans, but still routes many customers through quote-based packaging designed to upsell distribution scope and add-ons (Business Wire pricing: ).

The pricing model itself reveals the incentives. Most major wire services charge a flat fee per release and then layer on add‑ons: longer word counts, more regions, more “premium pickups,” more compliance packaging, more translations, more images, and more “guaranteed placements.” The buyer is encouraged to keep upgrading because every add‑on looks like additional reach, even when the underlying distribution is still the same press‑release container infrastructure described earlier.

On vendor sites, the first thing you’ll notice is that pricing is rarely tied to audience. It’s tied to *format*. You are not buying access to a defined group of readers; you are buying the right to publish a block of text into a syndication pipe.

In some cases, vendors publish tiered plans openly. In others, pricing is quote‑based, which gives sales teams room to anchor high and upsell aggressively. Either way, the pattern is consistent: you pay more for the appearance of wider distribution, not for proven engagement.

And because the deliverable is often positioned as “earned media adjacent,” the internal justification becomes emotional instead of economic: *this makes us look legitimate.* That’s how $400 becomes $900, and $900 becomes $1,800 — for the same PDF‑shaped product.

The hidden cost is not just the invoice. It’s the time cost of writing, coordinating approvals, and chasing a narrative that never gets read — and the opportunity cost of not spending that same money on channels that can actually be tested, measured, and improved.

In the next section, we’ll look at the metric loophole vendors hide behind — and why “privacy” is the most convenient excuse in the world when your results are close to zero.

The Accountability Gap: What Real Media Buyers Expect

Here’s the simplest way to tell whether you’re dealing with a real media product or a credibility costume: ask for the same metrics any serious marketer would demand from a $1,500 spend.

If the answer is “we don’t track that,” you already have your verdict.

At minimum, a paid channel should be able to answer:

- Who saw it?** (audience definition)

- How many saw it?** (verified impressions)

- Did anyone engage?** (CTR, time on page)

- Did it convert?** (sign-ups, leads, installs, wallet connects)

- What did it cost per outcome?** (CPA, CAC, ROI)

- How many commercial results did it achieve?** (sales, sign-ups, revenue)

With performance media, those numbers are the product. You don’t have to ask — the dashboard is built around them.

With wire distribution, those numbers are often missing entirely. You’ll get a pickup report showing a list of endpoints, maybe a vague “estimated reach,” and occasionally a small click-tracking report if the vendor offers it as an add-on. The core deliverable is not engagement; it’s placement.

That is why “privacy” shows up so often in sales conversations. In Web3, vendors have learned they can frame the absence of tracking as a virtue — and most buyers won’t challenge it. But privacy is not a measurement strategy. It is an excuse.

If a vendor can’t show you who saw it, who clicked, and what happened next, the spend is not accountable. And if the spend is not accountable, it is not professional.

Section 3 conclusion: By now the pattern should be obvious. Press releases are priced like media, sold like credibility, and delivered like unmeasured distribution. If they can’t compete on metrics, they don’t deserve budget — especially when that budget belongs to investors, token holders, and stakeholders expecting a return.

And let’s be explicit about what “outcomes” means. Outcomes are commercial results: sign‑ups, leads, revenue, retained customers, and ultimately money returned to the people who gave you the budget in the first place. If it can’t connect to outcomes, it’s not a strategy. It’s wasted energy.

Metrics? Nah, We Do Privacy: The Most Convenient Lie in Web3 Marketing

If you’ve ever asked a press release vendor for performance data, you’ve heard the script.

They’ll tell you Web3 is privacy-first. They’ll say cookies are unethical. They’ll say crypto users don’t want to be tracked. They’ll say analytics “don’t really matter” because the goal is exposure. Many vendors will still quote “50M reach” while refusing to define the audience, disclose methodology, or show engagement — and based on VaaSBlock’s internal research, if those numbers are real at all, the most plausible interpretation is that they reflect total annual traffic to a domain, or a cumulative count across a site’s full history.

That isn’t privacy. It’s the absence of evidence. Many publisher pages list wire attribution and contain no visible engagement signals at all — no comments, no social shares, no editorial linking — because they are not meant to be read. The “privacy-first” script collapses the moment you remember what you’re actually buying: attention, which is measurable without identifying anyone.

This is an incredibly unprofessional posture — and it belongs to the legacy era of TV and radio, when audiences were inferred and “reach” estimates were accepted because measurement was genuinely hard. Digital media doesn’t work that way. The modern advertising industry has spent two decades standardizing what counts as an impression and what counts as a click, precisely because real money is on the line (IAB Click Measurement Guidelines; Google Ads click measurement methodology).

Even in a privacy-first world, measurement is not optional. Apple’s SKAdNetwork (and its successor frameworks) exist specifically to let advertisers measure campaign success using aggregated, privacy-safe data (Apple Developer Documentation — SKAdNetwork). Google’s Privacy Sandbox Attribution Reporting API exists for the same reason: conversion measurement without third‑party cookies or cross‑site tracking (Privacy Sandbox Help — Attribution Reporting API).

So when a vendor tells you they “can’t” provide article-level performance, the problem is not privacy. It is that they are selling a product that performs too weakly to survive honest comparison.

This is not an oversight — it’s the business model. If vendors provided the metrics that are easy to pull on their own sites, the reality would surface immediately: the vast majority of these pages get near-zero impressions. The con would be over.

Citations: IAB, “Click Measurement Guidelines”; Google Ads Help, “Description of Methodology”; Apple Developer Documentation, “SKAdNetwork”; Google Privacy Sandbox Help, “How the Attribution Reporting API works.”

When a project pays for distribution, it is paying for attention. Attention can be measured without violating anyone’s privacy. Every serious media platform does this: impressions can be verified, clicks can be tracked, time-on-page can be measured, conversions can be attributed — all without identifying individuals.

In fact, the advertising industry has spent the last decade moving in the opposite direction of surveillance: toward aggregated reporting, cohort-based targeting, and privacy-safe attribution. Apple’s App Tracking Transparency and Google’s shift away from third-party cookies didn’t end measurement — they forced it to evolve.

Here is what professional media buyers expect from any channel that charges four figures:

- Verified impressions (not “estimated reach”)

- Clicks and click-through rate

- Engaged time / time-on-page

- Traffic sources (where did the audience come from?)

- Conversion attribution (what happened after the click?)

- Cost per outcome (CPA / CAC)

Wire vendors rarely offer that. Instead, they offer one of three substitutes:

- Pickup reports — lists of sites where the release was reposted.

- Vanity reach numbers — “50M+ impressions” style estimates with no methodology.

- Privacy theatre — framing the absence of measurement as an ethical stance.

For example, EIN Presswire promotes “detailed distribution reports” and a tracking dashboard in its public pricing and marketing materials — yet even that is framed as optional reporting layered on top of a distribution product, not as proof of commercial outcomes.

The vendor excuse vs the professional response

| What the vendor says | What it really means | What a professional asks next |

|---|---|---|

| “We’re privacy-first, we can’t track.” | They don’t want to show weak engagement. | “Show aggregated page views, clicks, and time-on-page.” |

| “Estimated reach: 50M+ impressions.” | A vague site-level number, not page-level performance. | “What’s the methodology? What did this page get?” |

| “Look at the pickups — big logos.” | Syndicated endpoints, not editorial coverage. | “How many clicks and conversions came from each?” |

| “PR isn’t measurable like ads.” | They want immunity from accountability. | “Then we treat it as earned media — show coverage.” |

The trick is that all three substitutes sound like marketing to people who haven’t run real campaigns.

This is where the scam becomes visible.

Because if your product actually performed, measurement would be your strongest sales asset.

No serious media network hides its analytics.

And no professional marketer celebrates a channel that refuses to prove it worked.

In the next section, we’ll look at how this blindness becomes an SEO and credibility liability — and why press release spam can quietly teach search engines and LLMs to treat your domain as low-quality.

SEO Theater: The Backlink Mirage and the Quiet Cost to Trust

If press releases weren’t routinely sold as an SEO tactic, they would be easier to ignore. But in Web3, “SEO value” is one of the most common rationalizations used to justify paying thousands of dollars for wire distribution.

The logic usually sounds like this: a release gets syndicated across dozens of domains, those domains link back to your site, and Google rewards you with higher rankings. On paper, that story feels plausible. In practice, it rarely holds up.

SEO is not a one-off marketing expense. It is a compounding asset: the slow construction of a digital reputation that can produce organic demand for years. Done well, it increases the value of your company’s most important virtual property — your website — by earning recurring traffic from people actively searching for solutions and ready to convert. Done poorly, it creates a drag you can’t see until it’s too late. And because it compounds over time, the cost of getting it wrong is rarely a single invoice — it’s months or years of lost opportunity. That matters when you’re spending other people’s money and you’re accountable for turning that budget into commercial return.

The first problem is structural. Most press release pickups are tagged nofollow or sponsored, which means search engines are explicitly told not to treat them as editorial votes. Google’s own guidance on link attributes makes the intent explicit: nofollow and sponsored links are signals that a link should not pass ranking credit in the same way an editorial reference would. Google has been clear for years that links intended to manipulate rankings violate its spam policies — and press-release-style link campaigns fall directly into that category. Google’s own examples of link spam explicitly include “links with optimized anchor text in articles or press releases distributed on other sites,” which is effectively the default template many wire releases still follow.

Google doesn’t even leave this up to interpretation. It says it directly:

“Links with optimized anchor text in articles or press releases distributed on other sites.” — Google Search Central, examples of link spam

We don’t need to get into technical debates about whether press releases “help SEO” when Google straight up lists the tactic as spam.

If a vendor is selling releases as “link building,” they are selling you a tactic Google has already classified as spam behavior. (Google Search Central, “Link spam”) (Google Search Central, “Link best practices” and “rel=nofollow” guidance)

The safest interpretation is simple: if you’re buying press releases for “SEO,” you’re paying for a tactic Google has repeatedly warned against.

SEO professionals have been blunt about this for years: press release syndication is not a reliable link-building strategy. It can create visibility for a genuinely newsworthy announcement, but the links themselves are typically nofollowed, syndicated, and treated as low-value by search engines. In other words, a press release can amplify news — but it does not manufacture authority.

The second problem is duplication. Wire releases are copied verbatim across low-value endpoints. Search engines learn to treat those pages as templated, syndicated content — which means they rarely rank, and they rarely transfer meaningful authority. Ahrefs has repeatedly pointed out that press release links tend to be nofollowed, low-value, and unlikely to move the needle unless the story itself earns genuine editorial coverage. (Ahrefs, “Press release backlinks”) Semrush similarly notes that press release syndication may create lots of backlinks, but most are low authority and contribute negligible SEO value unless they lead to real mentions and real links. (Semrush, “Press release SEO”)

In other words: the press release doesn’t rank because it’s a press release. It ranks only when it becomes news.

That distinction is not academic. When press releases “work,” what’s really happening is that the release is riding on external demand: a Tier‑1 partner’s brand gravity, a breaking narrative, or a story that would have earned attention anyway. In those cases, the SEO lift comes from search interest and secondary editorial mentions — not from the wire backlinks themselves. The release is empty messaging — not a ranking factor.

This is why your “best case” press release exception is almost always the same story: a major partner, a big brand, or a piece of information that journalists would have covered anyway. The press release is just a vessel.

At VaaSBlock, we’ve reviewed more than 600 Web3 projects. Only two press releases showed any measurable SEO benefit — and in both cases, the benefit came from the underlying narrative, not the wire distribution. One release involved a legitimate partnership with a Tier‑1 company, which naturally generated search interest and secondary coverage. The other benefited from clever phrasing that implied a deeper relationship with a major platform than actually existed. Even those two examples are not success stories. They are exceptions that prove the rule.

If you want a simple heuristic: wire links are cheap because they don’t behave like editorial links. They live in low-trust neighborhoods, are frequently nofollowed or syndicated, and they rarely earn follow-on citations. Real SEO wins come from real references — journalists, analysts, and credible sites choosing to cite you in context. That is the kind of signal search engines and retrieval systems are designed to reward.

And there’s a quieter cost: trust.

If you want SEO lift, earn real editorial mentions and citations that a credible third party chose to make — not syndicated wire links.

That doesn’t mean a single press release will “tank your SEO.” The damage is subtler. It’s a slow erosion of credibility signals. A polluted link graph. A history of low-value associations.

This is what credibility decay looks like in slow motion — and in the case of wire releases, decay is often the only consistent outcome. While conducting this report, we found no evidence that the releases routinely used by crypto marketers provide meaningful SEO value.

The irony is that the same founders who obsess over domain authority and brand trust are often the ones paying to contaminate it.

And if you’re doing it with investor money, it’s not just waste — it’s misallocation.

Press releases don’t just waste money. They waste time — and SEO is time. If your marketing team is burning cycles on templated wire copy while your competitors earn real mentions and real links, you’re not just failing to grow your organic asset. You’re actively falling behind.

In the next section, we’ll look at the psychology behind this behavior — and why amateur executives keep buying a product that professional marketers would reject on day one.

The Psychology of Spam: Why Amateur Executives Love the Button

If press releases are as ineffective as the data suggests, the real question isn’t why vendors sell them — it’s why otherwise rational teams keep buying them. The answer is not strategic — it’s psychological.

Management research has long described how organizations use visible signals to manufacture legitimacy when trust is scarce — especially in markets where outsiders struggle to verify what is real. In those environments, symbolic outputs can become substitutes for performance, because they are easier to produce and harder to audit. (Harvard Business Review; MIT Sloan Management Review)

This isn’t PR. It’s insurance for insecure leadership — and the premium is paid in other people’s money.

A press release is the perfect product for a credibility-anxious organization because it creates an artifact that looks like progress. It produces a link. It generates a headline. It can be pasted into investor updates, forwarded internally, and celebrated in Slack. For executives under pressure, that visibility feels like momentum — even when nothing in the underlying business has changed.

And because it feels like output, it becomes a substitute for the harder work that actually builds companies: shipping, distribution, customer development, and earned attention.

This is also why press releases thrive in industries where legitimacy is fragile. Web3 is not competing only for users; it is competing for belief. In Web3, belief is a currency — and press releases are the cheapest way founders try to mint it. In markets where trust is scarce, anything that resembles trust becomes valuable — even if it is hollow.

This dynamic aligns with the 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer, which reports widespread distrust in institutions and a growing belief that leaders deliberately mislead the public — conditions that make legitimacy-signaling tactics more attractive than substance. (Edelman, *2025 Trust Barometer*; Axios, “Trust in CEOs erodes, new report shows.”)

That leads to four predictable mechanisms.

1) Legitimacy theatre. When credibility is scarce, teams buy symbols of credibility. A wire release offers the appearance of being “in the media,” even though it is structurally closer to self-publishing. It is credibility by adjacency — a logo, a screenshot, a page on a respected domain.

This is classic signaling behavior: when real credibility is expensive, teams buy cheaper symbols of credibility that look similar at a distance. (Harvard Business Review)

2) Screenshot economics. Web3 treats funding rounds, listings, and “strategic partnerships” as achievements in themselves. A press release converts these moments into a screenshotable asset that can be redistributed as social proof. The release is not built for readers; it is built for circulation among insiders.

The release is not designed to persuade outsiders. It’s designed to reassure insiders.

3) Deliverable addiction. Agencies and internal teams are judged by visible outputs. A press release is a clean deliverable: it has a start date, a finish line, and a link. It satisfies the organizational need for production — even when it produces no commercial outcome.

4) Career insulation. If a performance campaign fails, the numbers make the failure obvious and someone becomes accountable. Press releases offer a safer career strategy: if nothing happens, the marketer can claim “brand awareness” and hide behind reach estimates. The channel is attractive precisely because it is hard to audit.

This incentive pattern is not unique to Web3. Strategy and management reporting repeatedly warn that when teams are evaluated on activity rather than outcomes, organizations drift toward vanity metrics and “work products” that protect careers but don’t move the business. (MIT Sloan Management Review; Harvard Business Review)

This is what marketing looks like when nobody is accountable for outcomes.

This is why press releases are disproportionately common in amateur organizations. They reward the appearance of motion, not the production of outcomes.

And because the budget often isn’t theirs — VC money, token-holder money — the pain of waste is delayed, which is exactly why the habit survives.

It also explains why founders defend them. In a fragile credibility economy, admitting that a press release produced nothing is psychologically costly. So the activity becomes emotionally protected, and anyone questioning it is framed as cynical or “not understanding PR.”

But PR is not emotional. PR is strategic.

The strongest marketing leaders in Web3 will treat press releases the way serious CFOs treat waste: as a habit that exists only because no one has enforced accountability.

Meet the Sellers: The Wire Services Selling Optics as PR

Before we name names, one premise matters: Web3 almost never produces news that deserves a press release. Most projects are not announcing a discovery, a market-moving disclosure, or a breakthrough that changes how people behave. They are announcing a funding round, a partnership, a listing, or a feature that looks important internally but is invisible to everyone else. In other words, the probability that your announcement is genuinely newsworthy is close to zero — which means the probability that paying for distribution makes sense is close to zero too.

If you’ve made it this far, the logical conclusion is brutal: we’ve disproven every serious reason a rational team would buy a Web3 press release.

In fact, in most cases the expected value is less than zero: you pay for content that isn’t read, spend internal time that cannot be recovered, and risk teaching search engines and LLMs that your brand communicates like spam.

It fails as PR, fails as measurable media, fails as SEO — and in many cases quietly harms credibility.

So the obvious question becomes: **if the product is this weak, how do the sellers keep winning?**The answer starts with understanding who the sellers actually are.

There are two overlapping categories.

The first is the traditional wire services — PR Newswire, Business Wire, GlobeNewswire — originally built for corporate disclosure and newsroom distribution. These are legacy infrastructure companies with real reach in regulated finance and large enterprise communications — and they now sell “blockchain” and “crypto” distribution packages because Web3 is one of the few categories where buyers still confuse distribution with journalism. (PR Newswire product pages; Business Wire pricing; GlobeNewswire distribution packages)

The second category is the one Web3 founders encounter first: crypto-native press release vendors that package the exact same infrastructure into a more aggressive, more seductive pitch. These companies position themselves as “Web3 PR specialists” while selling a commodity: press release distribution bundled with republishing on crypto news sites.

The names change, but the model is consistent. In practice, many operate like a web3 PR agency in name only — selling distribution while implying editorial endorsement.

Chainwire is a perfect example. It brands itself as a “crypto PR distribution” provider and sells multi-release packages, pickup promises, and tiered placements on crypto publication networks — the same screenshotable adjacency the industry has been conditioned to mistake for credibility. (Chainwire marketing pages; Chainwire pricing / packages — including Chainwire pricing that scales with “tier” placements —; Chainwire pricing page)

And Chainwire is not alone. The broader ecosystem includes services like Coinzilla’s PR distribution, BTCWire, CryptoPR, ChainPR, NewsBTC PR, and agency-style hybrids that sell “press release + guaranteed placements” bundles as if they were real earned media. (Coinzilla PR services; BTCWire distribution; CryptoPR packages; ChainPR site; NewsBTC press release services)

The pitch is always framed around three levers:

- Reach claims (“seen by millions”)

- Logo adjacency (“featured on” lists)

- Tiered placement (basic, premium, top-tier)

Some vendors publish pricing openly. Others quote it privately to anchor high, upsell packages, and price-discriminate based on how much money a project has raised.

And nearly all of them sell the same emotional outcome: the feeling of being legitimate.

This is why the crypto-native vendors outperform the mainstream wires in Web3. They don’t sell distribution. They sell reassurance.

How They Sell It: The Script, the Sleight of Hand, and the Accountability Escape Hatch

The sales pitch is remarkably consistent across vendors because the product is remarkably similar. Whether the logo on the invoice says Chainwire, EIN Presswire, ACCESS Newswire, or a boutique “Web3 PR agency,” the mechanics barely change.

The pitch begins by borrowing the language of credibility.They don’t say “advertising.” They say “PR.” They say “media coverage.” They say “distribution.” They say “visibility.” They say “authority.” The goal is to keep the buyer thinking this is earned media adjacent — something you buy once and it sticks.

Then they show you the logo wall — the oldest trick in the deck.The slide deck always looks the same: glossy gradients, a logo wall, and one huge reach number in bold. A slide full of recognisable brands — Yahoo Finance, MarketWatch, Benzinga, Business Insider, Cointelegraph — presented as if those publications will *cover you*. Sometimes the pitch even uses the word “featured.” In reality, these are mostly republishing endpoints: press-release containers that accept syndicated feeds and automatically publish wire copy under a disclosure label. The logo wall works because it exploits a truth most Web3 buyers don’t understand: a respected domain can host your text without endorsing it.

Next comes the reach number.This is where the pitch becomes audacious. “50M+ reach.” “Guaranteed impressions.” “Millions of readers.” The number is rarely tied to a page, an audience, or a methodology. In some cases, it appears to be a total traffic estimate for the entire host domain — or worse, a cumulative number that could only be achieved by adding up site traffic across the full distribution network. Chainwire’s own pricing deck makes the value proposition explicit: “Homepage coverage guaranteed” and automatic publishing to “100+ crypto news sites,” language that sells placement as if it were attention. (Chainwire pricing PDF; Chainwire pricing page)

This is why the entire category is scam-adjacent: the vendors are selling an outcome — legitimacy — while carefully avoiding the only evidence that could verify it: readership, engagement, and measurable referral traffic.

If you ask for article-level engagement, the story changes.

This is where “privacy” enters the script.

The vendor will say they can’t provide page views, clicks, or time-on-page because Web3 is privacy-first. They’ll say cookies are unethical. They’ll suggest that analytics are “not the point,” because the value is exposure. But privacy-safe measurement exists across the entire modern advertising economy. The absence of reporting isn’t a technical limitation — it’s a commercial necessity.This is not an oversight. It’s the business model. (PR Newswire wire distribution explainer; PR Newswire Visibility Reports documentation)

If vendors provided the metrics, the reality would surface instantly: most press-release pages receive close to zero meaningful attention, and the ones that receive attention do so because the story itself was strong enough to generate demand.

Then comes the lock-in: the package.You’re rarely sold one release. You’re sold a campaign. Five releases. Ten releases. A “monthly presence.” A content calendar. Once a team buys the first release, the next sale becomes easier because the deliverable is already justified internally. This is how vendors lock in recurring revenue: not by proving outcomes, but by embedding the activity into the culture.

By the time the deal closes, the buyer has been guided away from the only questions that matter:

- How many people actually read this?

- Who were they?

- What did they do next?

- What did it cost per outcome?

And that’s the point.

Wire vendors are selling a product that behaves like media, but they protect it from being evaluated like media.

They are not selling you attention.They are selling you the illusion of attention — and the paperwork to justify it. The pickup report is where that illusion becomes a deliverable.

In the next subsection, we’ll get even more specific: how the republishing network works, what the “pickup reports” actually prove, and why the strongest proof of a press release’s value is usually the same thing vendors cannot provide — a measurable outcome.

The Pickup Report Illusion: Distribution Without Readers

After a press release runs, most vendors send what they call a “pickup report.” It usually looks impressive: a long list of logos, domains, and URLs where the release supposedly “appeared.” To an inexperienced founder, it reads like proof of impact. A typical pickup report lists 40+ endpoints but provides no verified readership — no page-level impressions, no time-on-page, no referral traffic, and no outcomes.

It looks like proof of impact. It isn’t.

A pickup report is not a readership report. It is a syndication receipt.

PR Newswire’s own Visibility Reports documentation defines “exact match pickup” as full-text reposting of your release by syndication partners — in other words, duplication, not independent coverage. (PR Newswire Visibility Reports — Pickup definition)

That’s why pickup counts can look huge while readership is close to zero — you’re measuring duplication, not demand.

It tells you where the wire feed was ingested — not whether anyone read it, engaged with it, or acted on it.

In many cases, the pickup list is dominated by the same kinds of endpoints we mapped earlier: press rooms, IR subfolders, syndicated newswire pages, and low-traffic PR archives. These pages exist because they are cheap to run and easy to monetize, not because they attract meaningful audiences.

This is also why pickup reports are such a convenient deliverable: they convert “distribution” into something that looks like performance.

Performance media doesn’t work that way — and that gap is the entire con.If you buy ads, the report shows verified impressions, clicks, and conversion events. If you buy sponsored content from a credible publisher, you get pageviews, time-on-page, and referral traffic. If you pay for a newsletter placement, you get opens and CTR.

A pickup report gives you none of that. It gives you a list — and the list is often padded, duplicated, and misleading in subtle ways.Some pickups are duplicates: the same publisher domain appears multiple times across different subfolders, different feeds, or mirrored endpoints.Some pickups are low-value “news” aggregators that exist primarily to republish wire copy.Some pickups are technically live but practically invisible — unindexed, unlinked, and never distributed beyond the wire feed itself.And some pickups are not pickups at all, but “potential pickups” — sites where the vendor claims the release *may* be distributed depending on feed rules and editorial filters.In other words: the pickup report is designed to maximize perceived reach, not to verify outcomes.

A pickup report proves your copy was uploaded. It does not prove it was read.

What pickup reports prove vs what they don’t

| What the vendor shows you | What it proves | What it does not prove |

|---|---|---|

| A list of pickup URLs and logos | The release was syndicated into endpoints | Any meaningful audience saw it |

| “As seen on” publisher logos | Your text appeared in a press-release container | A newsroom endorsed it |

| “Estimated reach” numbers | A vague site-level traffic estimate | Page-level impressions or engagement |

| “Distribution network” claims | Feeds exist and can ingest releases | That the feeds have readers |

| “Pickup report delivered” | A deliverable was produced | That the spend was justified |

If you want to test this yourself, open any pickup URL and look for signals of real readership: social shares, comments, internal linking from editorial pages, related story modules, or measurable referral traffic in your analytics. Most wire pickups have none of these signals because they are not designed to be read.

They are designed to exist, not to be read — and that distinction is the entire point of the wire model: wire releases optimize for publication, not attention.Which is why vendors can sell you distribution without ever being forced to prove readership.

In the next subsection, we’ll show how these “press release containers” are intentionally isolated inside publisher domains — and why that structural isolation is exactly what makes them safe for publishers and useless for you.

The Press Release Container: Why Publishers Isolate Wire Copy (and Why That Matters)

The most revealing detail about the press release economy isn’t what vendors claim — it’s how publishers structure the pages.

If these releases were real journalism, they would live where journalism lives: in the editorial flow of the site, connected to related stories, linked from category pages, and surfaced through the same distribution mechanics that drive actual readership.They don’t.

Instead, press releases are quarantined.They are pushed into subfolders labelled “press release,” “newswire,” “provided by,” “sponsored,” “PR,” or “press room.” They are often separated from the main navigation. They are rarely linked from editorial articles. They are frequently missing the modules that signal real audience behavior — no comment threads, no related coverage, no newsroom author profiles, no visible curation.This isn’t accidental. It’s a defensive design choice.

Large publishers understand exactly what these pages are: low-quality, high-volume, advertiser-funded content that can generate incremental impressions without risking the credibility of the newsroom.So they contain it.

It’s the same logic airports use to keep duty-free perfume booths away from security lines: the product is allowed to exist because it makes money, but it is kept at a distance so it doesn’t contaminate the core experience.

This architecture serves three purposes for publishers:

1) It protects editorial trust. The disclosure labels and isolation are a legal and reputational firewall. The newsroom can claim distance, and readers can see the content is not reported.

2) It monetizes the long tail. Wire copy costs nothing to write, requires no editing, and can be served ads indefinitely. Even if a tiny percentage of users stumble into these pages, the marginal revenue is still positive.

3) It keeps the vendors happy. The publisher gets paid indirectly through the wire ecosystem, and the vendor gets to include the domain in a pickup report.

The key point is this: the containment structure is the strongest evidence that publishers do not consider wire releases to be journalism.

And it creates a problem for buyers.Because search engines and retrieval systems learn from structure.

If your brand is repeatedly associated with templated wire pages in isolated, low-trust folders — alongside dozens of other projects making similar claims — that becomes part of your domain’s footprint.

This is where the credibility harm compounds. The release doesn’t just fail to build authority. It teaches machines that your communications look like spam.

In Web3, where bots and agents increasingly mediate discovery, that matters.The tragedy is that most founders never see this architecture. They see the host domain. They see the logo. They assume endorsement.But the publisher’s structure is telling you the truth.It is saying: we will host this, but we will not stand behind it.

In the next subsection, we’ll translate this into practical action: how to audit a vendor’s claims, how to verify whether a release was actually read, and what questions to ask that most wire sellers cannot answer.

The Audit Checklist: How to Verify a Vendor’s Claims in 10 Minutes

If you take one thing from this section, take this: **a press release vendor is not entitled to your trust.** If they want your budget, they should be able to answer the same questions any professional media buyer would ask.

If your announcement isn’t truly groundbreaking, a press release is not just a waste — it’s a negative-sum trade against your investors’ money.Most can’t.

Below is a simple audit checklist you can run in under ten minutes. It doesn’t require special tools — just common sense, a browser, and the willingness to treat “reach” claims as guilty until proven innocent.

The five questions every vendor must answer

1) Show page‑level performance, not network‑level estimates.

- Ask: “How many verified page views did the release receive, on each endpoint, and what was the average time on page?”

- Red flag response: “We don’t track that.” or “We’re privacy-first.”

- Professional minimum: aggregated page views, clicks, and time-on-page — no personal data required.

Define the audience.

- Ask: “Who is the audience, and how do you know?”

- Red flag: reach numbers with no breakdown by geo, interest, device, or distribution channel.

- Professional minimum: audience definition, even if broad.

3) Prove that the pickups were real, and not release duplicates.

- Ask: “How many unique domains picked this up, and how many are duplicates or mirrored feeds?”

- Red flag: pickup reports that count the same publisher domain multiple times across subfolders.

- Professional minimum: unique endpoint count, deduplicated.

4) Show traffic and outcomes — not just publication.

- Ask: “How many clicks reached our site, and what happened after they arrived?”

- Red flag: “Exposure” without referral traffic.

- Professional minimum: referral traffic + UTM tracking + goal completions.

5) Explain what would count as failure.

- Ask: “What performance threshold would make you refund or credit the release?”

- Red flag: no threshold, no guarantees, no accountability.

- Professional minimum: a definition of success and failure.

The 60‑second reality check (do this yourself)

Pick one pickup URL and inspect it like a journalist would.

- Does it sit in a folder labeled press release, newswire, provided by, or sponsored?

- Is there an author profile, editorial category linking, or related story module?

- Are there social signals — shares, comments, inbound links from real articles?

- Does the page look templated and identical to hundreds of other releases?

If the answer is yes, you’re looking at a press-release container. You bought publication, not attention.

Vendor claim → what it means → what to demand

| What they claim | What it really means | What to demand |

|---|---|---|

| “50M reach” | A vague site-level estimate, often cumulative | Page-level impressions and methodology |

| “As seen on Yahoo/Insider” | Your copy was hosted, not covered | A journalist-written article or referrer traffic |

| “Guaranteed pickups” | Syndication into endpoints, not readers | Unique domains + traffic per endpoint |

| “SEO value” | Mostly nofollow / duplicated links | Follow links from real editorial citations |

| “Privacy-first — no analytics” | No proof of performance | Aggregated metrics or don’t buy |

The one sentence that ends the conversation

If you want a clean way to stop the pitch, use this:“If you can’t connect this spend to outcomes, it isn’t PR — it’s wasted energy.”This is the professional standard.And it’s the standard wire vendors are structurally built to avoid.

Red Flag Roundup: Spot the Rookie the Moment the Release Drops

Press releases aren’t just a waste of budget. They’re diagnostic.They tell you what a team is optimizing for: evidence, or optics. And in Web3, optics are often the first refuge of companies that don’t yet have product truth.If you want to assess the maturity of a Web3 project — as an investor, a partner, a journalist, or even a candidate considering a role — you don’t need a deep audit. You can often tell within minutes by watching what they choose to announce, how they announce it, and how often they need the wire to manufacture legitimacy.

The fastest shortcut is simple: watch how often they press “publish” instead of shipping.Below are the most common press‑release tells — and what they usually signal.

The outcome test is simple: if the release didn’t trigger inbound enquiries from journalists, didn’t produce a measurable uptick in referral traffic, and didn’t move revenue, it was waste. And if the money came from investors or token holders, that waste is not abstract: you failed your responsibility to turn their capital into return. You also burned valuable time on an activity with a near-impossible chance of success, which means the real problem is often operational, a lack of internal standards, a lack of measurement discipline, or a team culture that rewards outputs over outcomes.

Red Flag #1: “Strategic partnership” with no meaningful detail

If the partner isn’t Tier‑1, the integration isn’t unique, and the announcement contains no concrete product change, you’re looking at a credibility exercise.

Example: a release announcing a “strategic partnership” with a liquidity provider or market maker — something any token can integrate in a day — presented as if it were a milestone.

What it reveals: leadership that confuses adjacency with progress.

Red Flag #2: “Raised $X” as if funding is the product

Funding rounds are not inherently newsworthy. They are a means to an end. If the release treats capital intake as the milestone, it usually means the company has nothing else strong enough to stand on. When a project treats capital intake as the milestone — and pays to publish it — it often suggests the team values validation over execution.

Translation: a company optimizing for perception, not outcomes.

Red Flag #3: Exchange listings framed as legitimacy

Tier‑9 exchange listings are not adoption. They are access. If a release reads like the listing itself is a breakthrough, it usually means the project has no real usage to talk about.

Example: a “listed on X” headline where X is a low-volume exchange, the listing was paid, and the only measurable outcome is a temporary spike in Telegram activity — not sustained trading or users.

The subtext: low traction disguised as momentum.

Red Flag #4: “As seen on” badges built from wire pages

If a project’s homepage has a wall of logos and those logos trace back to press‑release containers, it’s not credibility — it’s costume. It’s the crypto equivalent of renting a suit for an ID photo. Polished on the surface, empty underneath.

Example: a homepage logo wall that includes Business Insider — but the link leads to a “Provided by PR Newswire” wire page in a press-release folder, not a journalist-written article.

Spoiler alert: if you care about the “As seen on” effect, you could simply add the logos without paying anyone — no one will check, and no one will care. That is frankly no less true than paying for a wire page, because (1) “as seen on” is a lie when no one saw it — if your vendor disagrees, ask them for page-level numbers — and (2) the publication did not endorse you by hosting a labelled press-release container. The logo wall is not credibility. It’s costume. And it usually proves only one thing: someone inside the organisation still believes optics can substitute for trust.

What it really means: an organization buying legitimacy instead of earning it.

Red Flag #5: High frequency releases with no corresponding adoption

One release per month is almost never justified. One release per week is a crisis.A company that needs weekly wire copy is usually trying to out-run silence.

When a project needs constant wire publication to maintain the appearance of motion, it’s usually because the underlying business is not producing genuine signals of progress.

What it suggests: a team substituting noise for traction.

Red Flag #6: Generic hype vocabulary and templated narratives

“Revolutionary.” “Next‑gen.” “Disrupting.” “Leading provider.” “The future of Web3.”

When the copy sounds like it could describe any project, it usually means the project itself can’t articulate a real edge.

What it exposes: weak strategy and weak differentiation.

Red Flag #7: Vendor language inside internal communications

If you see phrases like “50M reach,” “guaranteed coverage,” “premium pickups,” or “Tier‑1 distribution” repeated internally, you’re looking at a team that has adopted vendor framing as truth.When marketing adopts vendor language, the vendor has already won.

What it tells you: a marketing org operating under influence.

Red Flag #8: No measurable follow‑through

he most telling moment is what happens after the release.

If the team doesn’t track referral traffic, doesn’t measure conversions, doesn’t report outcomes, and doesn’t run any follow‑up campaigns — the press release wasn’t part of a strategy. It was a checkbox. Checkbox marketing is what happens when nobody is accountable for outcomes.

What it indicates: amateur marketing and poor accountability.

Red Flag #9: Press releases used to fill investor updates

If the primary audience for a release is internal — investors, advisors, Telegram, Discord — it is not PR. It is internal theatre.

The real signal: credibility anxiety and runway pressure.

Red Flag #10: “Media coverage” claims with no journalist involved

If the release is the coverage, the project has no coverage.

Reality: a company mistaking publication for journalism.

If you are a founder reading this, take it personally: you are accountable for how investor money is spent. A press release is not a harmless mistake. It’s a signal that your leadership team is willing to buy optics in place of measurable progress.

The simple rule

If a release doesn’t contain a story that a newsroom would *choose* to report, it isn’t PR. It’s self‑publishing.

And if a project relies on self‑publishing to look legitimate, it should change how you interpret everything else they claim.

If you want to understand why this confusion persists, we need to define what PR actually is — and what Tier‑1 PR work looks like when it’s done properly. Real PR Doesn’t Have a Price Tag — It Has a Rolodex Here’s the sad reality: the press release is not PR.

In Web3, founders and marketers treat PR as a bundle of wire blasts and KOL tweets — a ritual of “published” links and (so‑called “social proof,” rarely defined or measured). But in professional communications, a press release is just one tool in an arsenal, and it only matters when it supports a strategy that can earn attention.

Real PR is relationship-driven, narrative-driven, and relentlessly outcomes-aware. It’s the work of shaping how a market understands you — not by buying placement, but by earning trust in the rooms where credibility is actually minted.

Journalists don’t treat releases as coverage — they treat them as a starting point for reporting. As the Poynter Institute puts it: “Think of press releases as a good starting point.” The work that follows is verification, context, and story. It is an invitation to a party — but until the journalist turns up with more questions, it’s just an unanswered invitation. (Poynter

That’s why Tier‑1 PR is fundamentally relationship capital. As FleishmanHillard’s global strategic media relations lead Trine Hindklev said: “When you have a relationship, you’re not just a name in an inbox… You’re someone a journalist knows will deliver the right story at the right time — and get it right.” (PR Daily)

A line often attributed to former Apple executive Jean‑Louis Gassée captures the core difference: “Advertising is saying you’re good. PR is getting someone else to say you’re good.” Attribution sources: (AZQuotes ; RJL Solutions )

Put simply: a press release is an invitation — real PR is the party.

What Tier‑1 PR work actually looks like (top level)

A serious PR lead — the kind who works with Apple, NVIDIA, Coca‑Cola, or global finance brands — spends most of their time doing five things:

1) Building and maintaining journalist relationships. Not one‑off “pitches,” but long-term credibility. They become a reliable source, so journalists call *them* when a story breaks.

2) Mapping narratives to real-world proof. They don’t start with a release. They start with the question: *what is true, what is new, and what will matter to the public?* Then they build proof — data, customer stories, demonstrations — that can survive scrutiny.

3) Preparing executives to be quotable and useful. Real PR creates executives that journalists want to cite: clear, accountable, and capable of saying something meaningful under pressure.

4) Orchestrating campaigns across channels. Earned media is supported by owned media, paid amplification, events, podcasts, analyst briefings, partner marketing, and internal alignment. The press release, if it exists at all, is just the record — not the strategy.

5) Measuring reputation like a business asset. Tier‑1 PR doesn’t hide behind impressions. It tracks coverage quality, message pull‑through, referral traffic, branded search lift, analyst mentions, lead quality, and pipeline influence.

A day in the life (what this looks like in practice)

Imagine a real story drops: a major product breakthrough, a significant security disclosure, a partnership that changes distribution, or a piece of data the market didn’t have yesterday.

A Tier‑1 PR lead doesn’t publish and pray.They draft the release to ensure accuracy and disclosure, yes — but within hours they’re on the phone with journalists they’ve cultivated for years. They’re briefing an editor who trusts them. They’re offering exclusives, context, and interviews. They’re helping a reporter write something real, not repost something templated. And in parallel, they’re coordinating the rest of the campaign: executive interviews, partner comms, social framing, paid amplification, and internal messaging so the company speaks with one voice.

This is not “distribution.” It’s strategy.“Think of press releases as a good starting point” Poynter Institute (journalism reality).“When you have a relationship, you’re not just a name in an inbox… You’re someone a journalist knows will deliver the right story at the right time — and get it right” Trine Hindklev, FleishmanHillard (relationship capital).“Advertising is saying you’re good. PR is getting someone else to say you’re good” AZQuotes & RJL Solutions

Compare that to how Web3 uses press releases

Most Web3 releases are written for internal reassurance and vendor packaging — not for newsrooms.They announce things that aren’t news. They use hype language instead of proof. They avoid scrutiny rather than invite it. They are written by the least experienced person in the chain, approved by people who don’t understand journalism, and sold by vendors who don’t have to prove outcomes.

A real PR professional would use a press release *only* when the story is genuinely newsworthy — and even then, the release would be the starting point, not the finish line. That’s the difference.Spend on What You Can Measure: The Anti‑Press‑Release Playbook

If you’ve read this far, the conclusion is unavoidable: press releases in Web3 fail on every axis that matters — they don’t earn coverage, they don’t produce measurable attention, they don’t build durable SEO authority, and they often teach search engines and LLMs to treat your domain like spam.So what should you do instead?

Forget the slogans — the only defensible standard is commercial outcomes, and every activity below is defined in a way you can measure.

The rule: if it can’t be measured, it doesn’t deserve budget

A serious marketing strategy can be explained in a single sentence:

Every dollar should either (1) bring a qualified person to your funnel, (2) convert them into a lead or user, or (3) increase the probability of revenue and retention.

If a channel can’t prove it did one of those things, you don’t have a strategy — you have expensive activity.

What to do instead (each with measurable definitions)

Below are practical alternatives to press releases. Every one has a measurable output and a measurable outcome.

ROI‑measurable alternatives to press releases

| Activity | What it is (definition) | What you measure (minimum) | What “success” looks like | Why it beats a press release |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search ads (Google/Bing) | Buying clicks from people actively searching high-intent keywords | CPC, CTR, conversion rate, CPA, ROI | Leads/users acquired below target CAC | Direct intent. Every click is trackable. |

| Retargeting (privacy-safe) | Reaching visitors who already engaged with your site/product | CPM, frequency, CTR, CPA | Lower CPA than cold acquisition; improved conversion rate | Turns existing attention into outcomes. |

| Sponsored placements (reputable pubs) | Paid placements with guaranteed distribution + reporting | Pageviews, time on page, CTR, leads | Verified distribution + measurable referral traffic | If you pay, you should get numbers. |

| Founder/executive appearances | Podcasts, panels, analyst briefings with real audiences | Referral traffic, branded search lift, lead capture | Spikes in branded search + inbound leads | Credibility is earned, not purchased. |

| Outbound to journalists (earned PR) | Targeted pitching to journalists with a real story | Reply rate, interviews booked, coverage quality | Journalist conversations + editorial coverage | The only PR that actually counts. |

| Original research / data drops | Publishing proprietary data others will cite | Backlinks (follow), citations, branded search | Earned citations + long-tail rankings | Converts expertise into authority. |

| Content built for conversion | Landing pages + case studies + docs that sell | CVR, time on page, assisted conversions | Higher conversion rate; lower CAC | Makes every channel perform better. |

| Partner distribution | Co-marketing with partners who already have your audience | Leads, conversions, partner-sourced pipeline | Qualified leads from trusted channels | Built-in trust + measurable results. |

| Community events with lead capture | Webinars, demos, workshops with registration and follow-up | Registrations, attendance, MQLs, SQLs | Leads that convert into pipeline | Real engagement, not publication theatre. |

| Product-led growth experiments | Referral loops, onboarding improvements, activation tests | Activation rate, retention, LTV, CAC | Higher retention + lower CAC | The compounding ROI engine. |

A simple budget example (ROI‑first)

If you have $10,000/month to spend, here’s a baseline distribution that prioritizes measurable outcomes:

- $3,000 — Search ads (high intent keywords; track CPA and ROI)

- $2,000 — Retargeting (warm users; optimize conversion)

- $2,000 — Content + landing pages (conversion rate improvements)

- $1,500 — Original research / data content (citations + backlinks)

- $1,000 — Founder distribution (podcasts / events with UTM tracking)

- $500 — Earned PR outreach tools (media database, outreach tracking)

This mix has a single purpose: measurable pipeline and compounding authority.And unlike press releases, you can adjust it weekly. If search ads are driving low‑quality leads, you change keywords. If retargeting isn’t converting, you change creative or landing pages. If content isn’t improving conversion, you rewrite it.Press releases don’t let you do that. They are flat‑fee bets with no feedback loop.

The commercial standard for your marketing team (or agency)

If you want to stop wasting money, your internal standard must change.Your marketers should be able to answer, clearly and quantitatively:

- What is our target CAC?

- What is our target LTV?

- What is our conversion rate at each stage?

- What channels are producing leads, and at what CPA?

- What campaigns increased revenue or retention?

If they can’t answer these, you don’t have a marketing function. You have output.And this matters because — again — it isn’t your money.Your budget likely comes from VCs or token holders expecting a return. That means every marketing decision is a fiduciary‑adjacent decision: you are allocating capital on behalf of others.

Hire for results, not “crypto PR experience”

One of the simplest fixes is also the most uncomfortable: hire marketers who have demonstrated a long track record of commercial outcomes.In a market flooded with narrative and noise, the only defensible marketing hire is someone who can prove outcomes.If a marketer cannot show outcomes across multiple cycles — not just one lucky campaign — they are not a growth hire. They are a risk.

Look for people who can show:

- years of statistically significant results,

- repeated wins across multiple cycles,

- real attribution discipline,

- and the ability to tie activity to revenue.